/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/39685838/455975570.0.jpg)

On Tuesday, at the UN climate summit, President Obama said the United States had cut its carbon-dioxide emissions "more than any other nation on Earth" over the last eight years. (That's sort of true, see here.)

"But," he added, "we have to do more."

So what does "do more" entail, exactly? Let's look at the big picture: The Obama administration has already promised to cut US greenhouse-gas emissions "in the range of" 17 percent between 2005 and 2020.

In his UN speech on Tuesday, Obama suggested the United States would come close to that 2020 goal — thanks in part to recent EPA regulations on vehicles and power plants. (The financial crisis and US shale-gas boom pushing out coal deserve credit, too.) Obama also mentioned a few smaller recent US actions to nudge emissions down further and address the impacts of global warming. Like:

- In an executive order signed Tuesday, all federal agencies will have to consider the future effects of climate change when providing aid and investing overseas.

- The White House will offer poorer countries new data tools to help better prepare for the impacts of climate change.

- The Obama administration has also announced a partnership with US companies to phase out the use of HFCs, a powerful greenhouse gas found in air conditioners.

But now comes the really difficult part: "By early next year," Obama said, the administration will outline broad goals for cutting US emissions after 2020. This is something that every nation has pledged to do by the spring as part of the next round of international climate talks. And in his speech today, Obama encouraged other nations to do the same.

The hope is that, by the end of 2015, there will be a new global accord that commits every country — not just the United States, but also Europe, India, China, etc. — to concrete reductions in greenhouse gases over the coming decades.

But that's all much easier said than done.

The US — and world — are still far from their climate goals

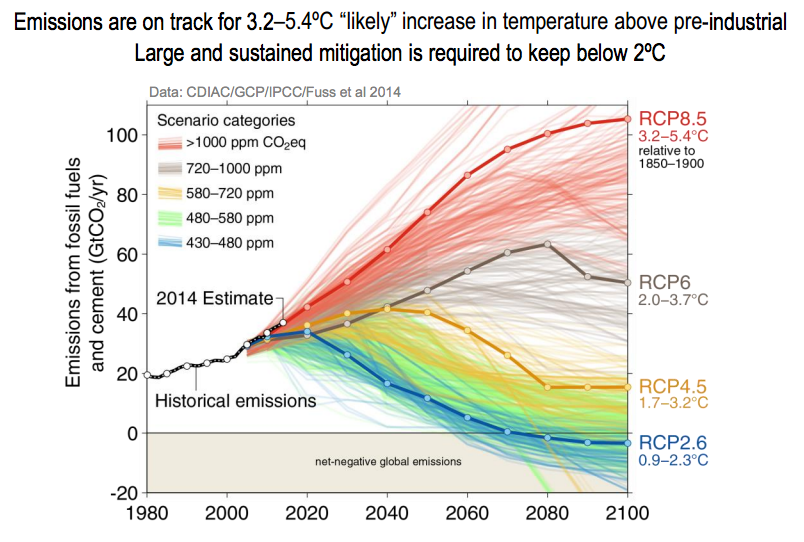

The world's leaders have already agreed that they want to avoid more than 2°C (or 3.6°F) of global warming. Go above that, the thinking goes, and we run unacceptable risks from sea-level rise, extreme weather, crop failures, and so on.

The only problem? If you add up everything that countries are already doing on emissions, we're on pace for between 3.2°C and 5.4°C of global warming — far above the target:

The world isn't doing nearly enough right now to meet its own climate goals. Emissions in the United States and Europe are falling slightly, but they're soaring in less-developed countries like China and India:

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/1374504/Annex_B_vs_non_Annex_B.0.png)

Now, there are a lot of ways to divvy up the blame here. The United States and Europe can say they're already taking some action, but now countries like China and India need to do more to curtail emissions. ("Nobody gets a pass," is how Obama put it in his speech, and added that the US and China have "a special responsibility to lead" as the two biggest emitters.)

For their part, developing countries like India often retort that wealthy countries have been enjoying the growth benefits of using cheaper fossil fuels for over a century now. Indeed, half the man-made carbon-dioxide that's currently in the atmosphere was put there by the United States and Europe. So those richer countries should be doing much, much more than they already are — America's modest 17 percent cut isn't nearly sufficient — and give developing countries more room to grow.

This is a deep and longstanding disagreement in global climate politics, and no one seems to have figured out how to solve it — not the Obama administration, not anyone. For now, Obama is mostly emphasizing the incremental progress that the United States has made on emissions and urging other countries to do likewise. But no politician has yet come up with a concrete plan to stay below 2°C of global warming.

"We have to raise our collective ambition," Obama said of the next climate pact. "It must be ambitious because that is what the challenge demands."

Meeting the 2°C goal would require very drastic changes

So what would "raising our collective ambition" actually look like? It would likely involve drastic changes to our energy system — changes that go far, far beyond any of the incremental policy measures Obama discussed in his speech.

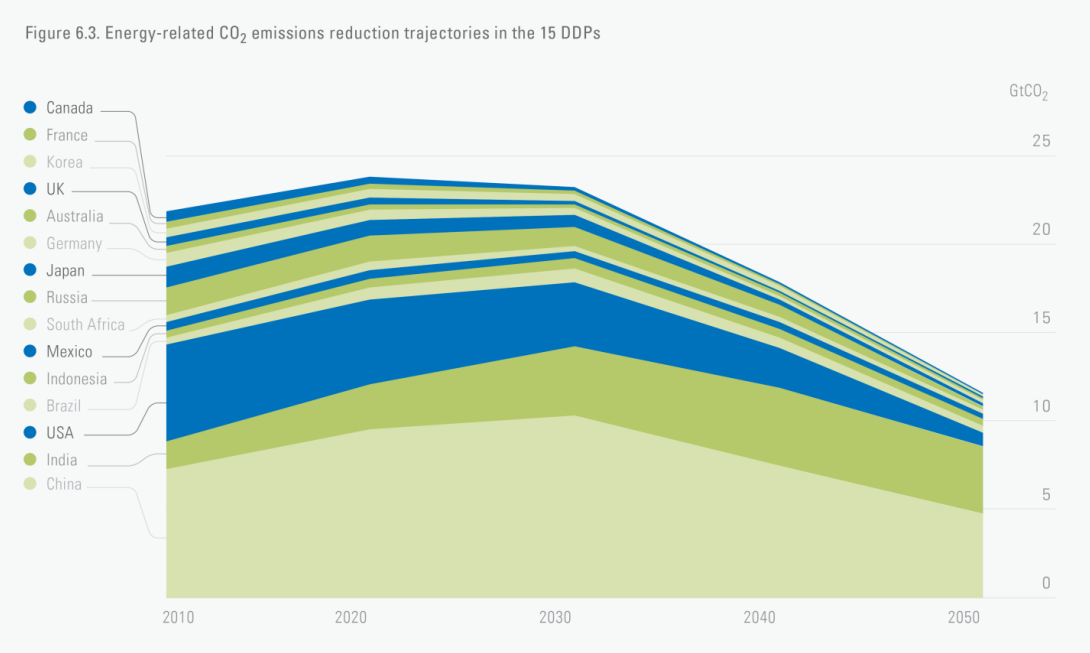

One detailed recent UN report on "deep decarbonization" found that the world's 15 largest economies would have to cut their emissions in half in the next four decades if the world wanted to avoid 2°C of warming.

That would mean the average person worldwide could emit no more than 1.6 tons of carbon per year by 2050 — less than one-tenth of what the average American currently emits.

(Deep Decarbonization Pathway Project)

In the United States, the report noted, that might mean getting 30 percent of our electricity from nuclear power and 40 percent from renewable sources like hydro, wind, and solar by 2050. Electric vehicles would need to handle about 75 percent of all trips. The coal plants that remained would all capture their carbon-dioxide emissions and bury them underground.

The UN report noted that a shift this wrenching was technologically feasible — though it becomes far more expensive if we rule out specific technologies, like nuclear or carbon capture for coal. (Another recent report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change pegged the costs of this sort of massive clean-energy shift at about 0.06 percentage points of growth per year, but only if all the technologies worked out well.)

In the United States, changes this big would likely require further legislation. But at the moment, virtually all Republicans and even many Democrats in Congress are unwilling anything to address climate change. The only things happening right now are incremental executive actions and speeches at the UN.

Further reading:

7 charts that explain why UN climate talks keep breaking down

Here's what the world would look like if we took global warming seriously

A longer look at the 2°C climate target