In Montana’s northwestern corner, centuries-old trees rise to a late September sky: ancient cedar, giant hemlock, shaggy sharp-needled spruce. Western larch, which can live for 1,000 years, tower above. Early morning’s light, filtered through the multilayered canopies, shimmers green and iridescent as it hits the forest floor, where bright ferns and mushrooms sprout from a carpet of blue lichen and emerald mosses. Mammoth fallen trees are slick with moss, their exposed root balls as big and round as a Volkswagen Beetle. The ground is so spongelike and moist that it squelches underneath my boots. A breeze moves through the overstory more than 150 feet above, and the forest creaks. A raven calls. A distant woodpecker drums its beak into a tree’s thick bark, foraging for beetles and ants. Otherwise this old-growth, primary forest is quiet.

Deep in a remote and rugged region known as the Yaak, this 192-acre expanse I am walking, unceremoniously called Unit 72 by the U.S. Forest Service, offers a rare glimpse of an original arboreal landscape. This is what the forests that cloak the surrounding mountains and valleys looked like before the axe and the chainsaw. For decades much of the region has been stripped of its timber, yet this lush section of old-growth forest appears to have never been logged, and there is no evidence that it has burned.

This stand, and a few others like it remaining in the Yaak, is vital habitat for grizzly bears and other threatened and sensitive species, as well as more common wild creatures and plants. Elk, moose, gray wolves, Canada lynx and the diminutive northern bog lemming (weighing in at a mere ounce) live here. Mayflies rise in clouds from the marshes and streams where otters play. Trumpeter Swans soar above.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Winters across the Yaak are typical of the Northern Rockies: bitterly cold with deep snowpack. But in the spring and fall, maritime weather drifts in from the Pacific Northwest, bringing clouds, fog and drizzle. The convergence of the two weather patterns results in a confluence of flora and fauna. As I step, I see the same tree species that grow along the coasts of Washington State, British Columbia and southeastern Alaska. I also see the lodgepole and ponderosa pines that thrive in the Rockies.

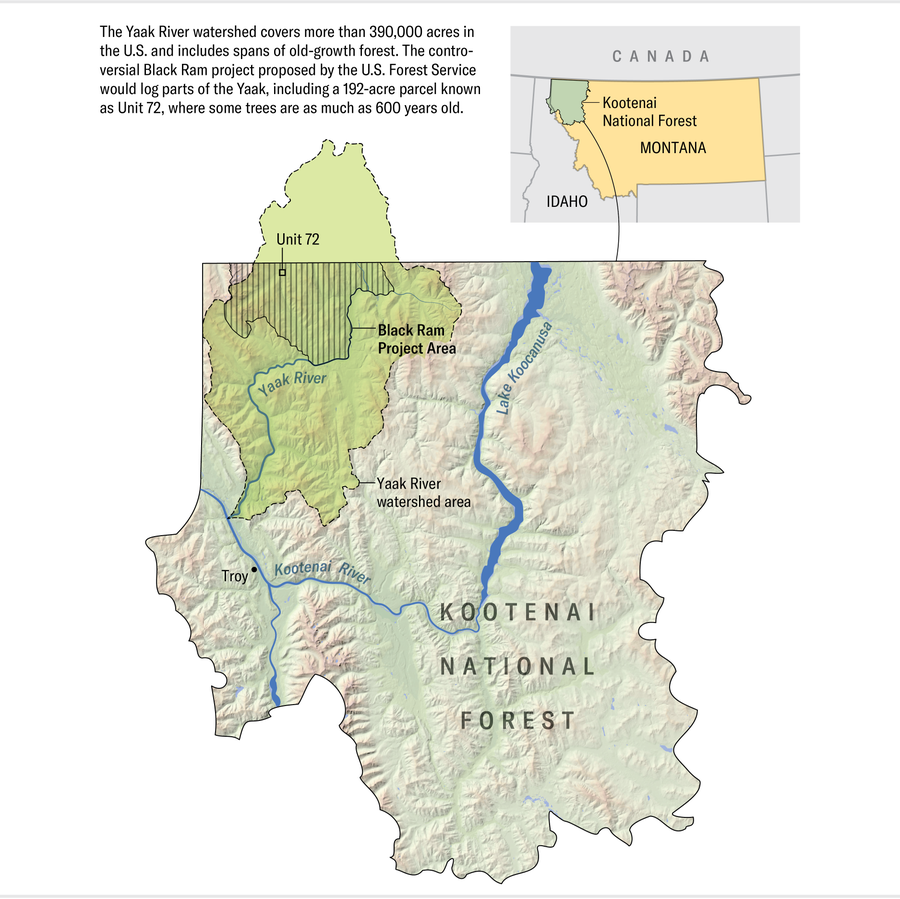

The name “Yaak” is derived from the native Kootenai term for “arrow” or “bow”—the same name given to the river that flows through the heart of this region. The USFS considers the Yaak River’s watershed—roughly 398,000 acres that touch Idaho to the west and British Columbia to the north—as the Yaak region, even though locals say it reaches much farther. Just 3 percent of the watershed is privately owned; the rest is part of the 2.2-million-acre Kootenai National Forest.

Logging began in the Yaak in the early 20th century with small-scale, family-owned mills. By the 1990s large corporations had replaced many of the local operations, and they have logged aggressively since then. In some areas, trees are selectively cut and removed, with others allowed to remain. Some tracts are clear-cut, leaving vast swaths of bare ground, desiccated streams and marshes, and countless tree stumps. Thousands of acres of the Yaak’s old-growth and mature trees have been clear-cut in the past 40 years.

The USFS manages national forests and grasslands on public lands across the country. The agency, housed under the Department of Agriculture, has long had a reputation for managing forests as crops. In 1986 timber was the highest-valued “crop” in the nation, a USFS report noted. The agency sells areas of forest—sometimes at below-market prices, according to various reports—to private logging corporations, sometimes at the expense of valuable ecosystems. The corporations harvest the wood and truck it away for profit. Today less than half of the Yaak’s primary forests remain uncut. Yet there is no official designation in place to protect the wild places that still exist.

Western red cedar (large tree) can grow to more than 200 feet tall, 20 feet in diameter and 1,000 years old. Timber companies seek the tree’s wood for decking, shingles and siding.

Credit: Chris Balboni

In the Yaak, the USFS has proposed or begun five major logging initiatives covering more than 300,000 acres in the Kootenai National Forest. For years various agencies, experts and politicians have promoted logging to prevent fire; a thinned forest, they argue, means there is less fuel to burn. The approach has been criticized, and fought, for just as long. One of the five projects, called Black Ram, was proposed in 2019 for the Yaak and blocked in August 2023 by a U.S. District Court judge ruling. Environmentalists say the 95,412-acre project, almost a quarter of the Yaak River watershed, would have allowed logging in hundreds of acres of old-growth forest—including Unit 72.

The potential loss is deeply unsettling to Rick Bass, my guide through Unit 72. Employed long ago as an oil and gas geologist, Bass is known to some audiences as an exceptional writer of literary fiction and essays often set in this wild region. Other people know him for his activism in defense of the Yaak. Bass the writer has published dozens of short stories and more than 30 books. He’s won multiple prizes and fellowships, including a Guggenheim Fellowship and a National Endowment for the Arts Literature Fellowship. Bass the activist has written editorials and articles about clear-cutting and roadbuilding in the Yaak, filed lawsuits against the USFS, and been arrested for civil disobedience multiple times, once in front of the White House.

Bass moved to the Yaak Valley from Mississippi at age 29 with his then partner, painter Elizabeth Hughes Bass, as they searched for a place to make their lives and their art. He describes the couple’s first season in The Book of Yaak (Houghton Mifflin, 1996). “We traveled through July thunderstorms and August snowstorms until one day we came over a pass and a valley appeared beneath us,” he writes, “a blue-green valley hidden beneath heavy clouds, with smoke rising from a couple of chimneys far below, and a lazy river snaking its way through the valley’s narrow center, and a power, an immensity, that stopped us in our tracks.”

Characters in Bass’s fiction hunt elk, deer and grouse. They fish the valley’s rivers and streams, they forage for berries and mushrooms, they gather firewood for the long, dark winters. These are not hobbies for his characters; they’re imperatives. Drawn to live in this sparsely populated valley, an hour’s drive on the easiest of days from the nearest doctor, grocery store, liquor store or post office, the characters are solitary and self-reliant, yet they are bound together by their shared craving for independence, wilderness and quiet, their shared love for this place, and their shared fluency in its ways.

Off the page Bass and his neighbors live the same way. Bass’s understanding of the land, his deep and intimate relationship with it, is evident as we hike. At 66 he is nimble and lithe as he scampers over the slippery carcasses of fallen trees and ducks under lodgepole pine blowdown, all the while pointing out species of trees and birds and answering my questions about forest policy, the ecological complexity that surrounds us and the fire resilience of old-growth woods.

We stop often, crouching to look at tiny ferns, bright orange mushrooms and elk scat. Huddled over a fungus that Bass says he’s never seen before, we notice a diminutive pygmy slug—a species, he tells me, that is not yet threatened but could be—making its long way over a rotting log.

At one point, when Bass is about 10 yards ahead of me, he shouts, “Oh, my god! Oh, my f------ god!” And then, “Come look at this!” As I reach him, he points to an enormous moose shed—a magnificent antler leaning against a downed tree, cast off by a male moose during the winter shedding season. One corner of it has been nibbled by some creature. “It’s a big one for this country. It’s huge! It’s one of the most beautiful things I’ve ever seen,” Bass says with enthusiasm and wonder. “It’s like a holy relic, as poetic a declaration to the Yaak’s wildness as anything.”

But then he grows quiet and points to the broad trunk of an ancient larch in a grove behind the moose shed. It’s been spray-painted with bright orange stripes—indicating that this stand of old-growth forest had been slated to be cut.

Bass describes Black Ram as a “holdover” of the Trump administration. In 2018 then President Donald Trump mandated increased logging in national forests, ostensibly to reduce wildfire. In 2021 another Trump-era rule went into effect allowing logging of old-growth stands in six national forests. Last September, Senators Joe Manchin of West Virginia and John Barrasso of Wyoming introduced bipartisan legislation to “reduce catastrophic wildfire risk and improve forest health,” largely through aggressive cutting.

Author and activist Rick Bass questions the practice of cutting down trees to lessen fire risk. Old-growth forests, he says, have survived wildfire for centuries without any human “help.”

Melanie Maganias Nashan

“They say they’ll log this old-growth forest—this wet, green rainforest—to create fire resilience,” Bass says, “but these trees are already fire-resilient. This larch, for example, is not only meant to survive fire; it’s meant to prosper from it. These attributes, the species diversity here, the structural diversity of the forest—they need to be studied, not clear-cut. But the Forest Service says that by clear-cutting a, what, nearly 1,000-year-old forest, they’ll teach it to be resilient?”

On Earth Day (April 22) in 2022 President Joe Biden issued Executive Order 14072, mandating an inventory of old-growth and mature forests on federal lands across the U.S. The order’s purpose was to create a policy to protect old forests. But even as the USFS and the Bureau of Land Management were tallying the trees, the two agencies continued to plan and implement logging projects like Black Ram in mature and old-growth forests across the country. These included nearly 10,000 acres of mature forest in Kentucky’s Daniel Boone National Forest and 54,883 acres of mature and old-growth trees in the Bitterroot National Forest, which extends from Montana across the Idaho border, roughly 250 miles south of the Yaak Valley. Bass says the Forest Service shows no sign of slowing down: “It flies in the face of the administration’s goal to conserve old-growth forests on public lands, not to mention the administration’s climate goals.”

The vast majority of old-growth forests in the U.S. have been logged, according to Dominick A. DellaSala, chief scientist at Wild Heritage, a project of the Earth Island Institute, and former president of the North American section of the Society for Conservation Biology. The untouched areas that remain include California’s 2,000- to 3,000-year-old giant sequoia and coastal redwood forests, northern Wisconsin’s 40-acre grove of 300-year-old hemlock and pine, and the scattered remnants of the 250-year-old post oak groves of the Western Cross Timbers forest, which once stretched from north-central Texas all the way into southern Kansas.

Perils exist worldwide. One of Europe’s last old-growth forests spans the border of Belarus and Poland, a remnant of the vast primeval woods that once cloaked the European plain; most of it is now threatened by logging, despite its also being a World Heritage site. There have been successes, too. The ancient temperate rainforest of Yakushima, Japan, prized for its cedar trees that are well over 1,000 years old and its extraordinary biodiversity, has been spared.

That Unit 72 ended up in danger is not a surprise to Bass. Twenty-seven years ago he and other residents of the valley founded the Yaak Valley Forest Council to protect the region’s remaining roadless areas and other critical habitat from roadbuilding and clear-cutting. When the USFS announced Black Ram, the council’s staff, board members and volunteers rolled up their sleeves yet again and got to work.

One of the council’s strategies was to prove the region’s old forests were indeed “old growth” and to demonstrate the forests’ capacity for carbon storage and fire resilience. The definition of old growth varies and can depend, in part, on the agency or organization doing the classifying. Most descriptions emphasize the forest’s age, its capacity to support exceptional biodiversity and its structural complexity—the presence of multiple features such as a multilayered canopy; a damp, hummocky forest floor; and standing dead trees and downed wood that create moist, fertile habitat for seedlings, fungi, insects and wildlife. Old growth can overlap with what’s called primary forests: woods of any age that have never been subjected to any industrial activities. According to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, since 1990 almost 200 million acres of the world’s primary forests have been destroyed—and every year many more acres of these already rare ecosystems are being lost.

DellaSala has studied the biodiversity attributes and climate benefits of mature and old-growth forests around the world. He visited Unit 72 at the council’s request after the USFS proposed the Black Ram project, to evaluate whether the unit was indeed old growth. “I can give you all kinds of stats and measurements, but it came down to this,” he says. “If it looks like old growth, it smells like old growth and it feels like old growth, it must be old growth. And Unit 72 sure was.”

The diversity impressed him. “There were big trees, small trees, midsize canopy trees. It was the perfect structure for an older forest.”

The day he went to the stand, DellaSala says, was beautiful “but hotter than hell. I remember just sweating bullets as we were walking along the road and through the clear-cuts. Then we entered the stand, and immediately it was like being in outdoor air-conditioning. The cooling effect of that stand—it really caught my attention.” Trees were covered with lichens and all kinds of bright mosses, “the diversity of plants that I would expect to see in an older forest,” he says. “And all that carbon tied up for centuries in the big trees and in the soils. Unit 72 was an easy write-up for me.”

The USFS approved the Black Ram project in June 2022. The Yaak Valley Forest Council sued the federal government in response, partnering with the Center for Biological Diversity and WildEarth Guardians. In January 2023 the Native Ecosystems Council and the Alliance for the Wild Rockies also filed a joint complaint. The plaintiffs asserted that the USFS violated the National Forest Management Act and the National Environmental Policy Act and did not adequately consider the project’s impacts on the region’s grizzly bears, a threatened species under the Endangered Species Act. They criticized the USFS for failing to prepare a full environmental impact statement, and they argued that the government didn’t consider the climate impact of logging the Yaak’s old-growth forests.

Credit: Dolly Holmes

Seven months later, on August 17, 2023, U.S. District Judge Donald Molloy blocked the agencies’ approval of Black Ram, largely agreeing with the plaintiffs’ claims. Every year temperate forests in the U.S. absorb about 15 percent of the country’s carbon emissions. Old-growth and mature forests are particularly effective. As a tree ages, its ability to sequester carbon increases, research has shown. Old-growth stands store 35 to 70 percent more carbon, including in the soils, than do logged stands. “Ultimately,” Molloy wrote in his decision, “removing carbon from forests in the form of logging, even if the trees are going to grow back, will take decades to centuries to resequester. Put more simply, logging causes immediate carbon losses, while resequestration happens slowly over time, time the planet may not have.”

Kristine Akland, Northern Rockies director and senior attorney for the Center for Biological Diversity, says the court ruling is precedent-setting. “This is the first time in the context of a timber sale that I’m aware of that a court has said that the Forest Service ... has to take a hard look at what projects like this actually mean for carbon sequestration, for carbon emissions.” Going forward, she notes, “for every single logging project, if not across the nation, then at least across Region One, the agency has to change its methods of analysis to include these questions.” Region One comprises 25 million acres of public lands that the USFS manages in northern Idaho, Montana, North Dakota, and parts of South Dakota and Washington State.

Akland adds that logging projects that target mature forests, not just old-growth ones, should be evaluated similarly. “The way we increase old growth is to protect the trees that are almost there.”

Other stakeholders in the Kootenai National Forest disagree with the court’s ruling, including Julia Altemus, executive director of the Montana Wood Products Association. “To say that old-growth forests are the answer to climate change—that’s not quite right,” she says. “They’re part of the solution. They’re certainly important.” Her group and others argue that trees lose carbon once they hit a certain age. But DellaSala says there is “no argument in the scientific community about sequestration.” Carbon sequestration, he goes on, “reaches a dynamic equilibrium in old-growth stands over time.” But it doesn’t decline. Individual trees, he says, “don’t stop accumulating carbon.... The larger the tree, the more surface area, the more carbon accumulates.”

For now the Black Ram project is stalled, but the USFS could “bring it back at any time,” Bass says, perhaps by changing the project’s plans a bit. Dan Hottle, press officer for USFSRegion One, says the agency is “still evaluating the court’s decision and determining next steps.” He also says that Unit 72 “does not meet the definition of ‘old growth.’” In the meantime, Bass and the Yaak Valley Forest Council are working with a network of scientists and environmental groups toward a move they hope will offer Unit 72 permanent protection and serve as a model for other old-growth forests around the country and across the world. Their goal is to have the forest designated as the nation’s first “climate refuge,” an area that remains relatively buffered from contemporary climate change over time and enables persistence of valued physical, ecological and sociocultural resources. In other words, Bass says, “it would be a sanctuary for wildlife and biodiversity and a tool for slowing climate change.”

The goal is lofty, Bass recognizes, but not unachievable. “The Forest Service and the Fish and Wildlife Service haven’t been shy about pursuing pilot or experimental projects,” he says. The priority should be “that the carbon-storing potential of these ancient forests—particularly in the northern latitudes and particularly at Black Ram—be protected with maximum urgency.” Moreover, “this forest doesn’t need our help,” Bass says. “It’s a natural solution for addressing the climate crisis just as it is. It is fire-resilient just as it is. Instead of worrying about the world burning, we can help cool it—by leaving this forest, and others like it, just as it is.”

A giant cedar binds the forest floor.

Credit: Chris Balboni

Leslie Caye, a member of the Kootenai, Yakama and Nez Perce nations, agrees. “It’s time to consider the concept of leaving things alone,” he says. “Let the forest be, without interference, without interruption.” Caye grew up on the Flathead Indian Reservation southeast of the Yaak and on the Yakama Reservation in Washington State. Today he develops Kootenai language and culture programming, as well as curricula for youth, on the Flathead reservation. The Yaak, he says, “is a part of our ancestral lands—lands that we lost, that were taken from us.” In times past, he says, “my people would go up there by the thousands to the Yaak Valley, and they would sing for a couple of nights in a row. For generations two forms of ceremony took my people there: the summer drumming ceremony that was part of our Sun Dance and what you might call, in layman’s terms, the vision quest, which helped us understand how to live as a Kootenai person. Our holy lands, you might say, are up there in the Yaak, including in Unit 72.”

Caye says, “We want to be able to return to that place, and other sacred places, to practice our cultural lifeways.... This is part of the process of reclaiming our identity as Kootenai people—that rejuvenating religious force that is the underpinning of who we are. But if the forest is being logged, how can we return there to practice our ceremonies? This, too, needs to be a part of the conversation.”

Last October, Bass unveiled a new tool he hopes can help save Unit 72 and old-growth forests everywhere. It was a guitar crafted by a renowned luthier from a length of a spruce tree that fell when the USFS cut a logging road to the edge of Unit 72. The guitar made its debut at the inaugural Climate Aid concert, in Portland, Maine, with a young American singer-songwriter, Maggie Rogers, performing with it. Today Bass carries the guitar to festivals and concert halls, schools and libraries across the country, where musicians play it, advocating for the future of old-growth forests. At each event, Bass asks, “Can a guitar save a forest?”

The morning after I walk Unit 72 with Bass, I begin the 10-hour drive to my home in south-central Montana, following the Yaak River to Highway 2. Mist clings to the forests, and the mountains are shrouded in clouds. In Troy, the first town I encounter, wood-smoke drifts upward from chimneys, and apples hang heavy from neighborhood trees. I buy a cup of tea for the road, and then I backtrack to the Troy Ranger Station just north of town to pick up some maps, including one of the Black Ram project. The receptionist is warm, friendly and generous, giving me a poster of pollinators as I leave after I commented on how beautiful it was.

I’m about a mile down the road when I see a moose step out of the thick forest. A logging truck coming the opposite way slows to a stop to let it cross, and so do I, but the moose turns and lopes back into the trees. I think of The Book of Yaak and a question Bass poses in it: “Settling in [to the Yaak] was not so much work and effort as it was relief, pleasure and peace. Does such a place exist for everyone? How many places are left in the world—what diversity of them still exists—and for that diversity, what tolerance, and what affinity?... What is the value of a place?”

It strikes me that the future of the Yaak’s old-growth forests, maybe the future of old-growth forests everywhere, might just hang on that question.