Cervical Screening: How It Works and Why You Need It

Key takeaways:

Cervical screening finds abnormal changes in your cervix that could lead to cervical cancer if not treated.

When cervical cancer is caught early, it is very treatable.

There are two main types of cervical screening: the Pap test and the HPV test. They are both easy to do and can be done during a regular pelvic exam.

Starting at age 21, all people with a cervix and uterus should start getting regular cervical screening.

Cervical screening is one of the most important steps you can take to stay healthy and cancer free.

Table of contents

Why trust us

Our Author:

Maria Robinson, MD, MBAMaria Robinson, MD, is a board-certified dermatologist and dermatopathologist with over 10 years of experience treating patients. She has a special interest in nutrition and how it can be used to treat disease and optimize health, and she has received training in nutrition and integrative health. She also serves as a consultant for different health technology companies and is active on several non-profit boards. Maria believes that education is the foundation for good health, and she enjoys helping others learn how to improve theirs. She can be found writing about skin and nutrition at DietandDerm.com.

For this guide, we reviewed national and international studies about cervical cancer and cervical cancer screening to evaluate which methods are most effective. We also reviewed the guidelines from major medical organizations and experts to bring together an overview of the best practices for cervical cancer screening.

What is cervical screening?

Cervical screening detects abnormal changes in your cervix that could lead to cervical cancer if not treated. Cervical screening has lowered the number of women who get cervical cancer and who die from it.

In the U.S., there are over 12,000 new cases of cervical cancer each year. There are different risk factors for cervical cancer, but the most important one is infection with human papillomavirus (HPV) — a common virus that can be passed between people during sexual contact. Cervical screening is the best tool to lower the risk of getting cervical cancer.

Cervical screening includes two different tests:

The Pap test (or Pap smear): A sample of cells from the cervix is examined for any abnormalities that could turn into cancer.

The HPV test: A sample of cells from the cervix is examined for any HPV strains that can cause cancer.

Both of these tests are done during a regular pelvic exam. They can be done together, but they don’t have to be.

It’s recommended that, starting at age 21, women get a Pap test every 3 years until they turn 29. Between ages 30 and 65, women can use different screening schedules: a Pap test every 3 years, or an HPV test every 5 years, or both tests every 5 years.

To keep yourself healthy, get to know:

What cervical screening is

What tests are available

How they’re done

When to get them

Here’s our guide to cervical screening.

What is cervical cancer?

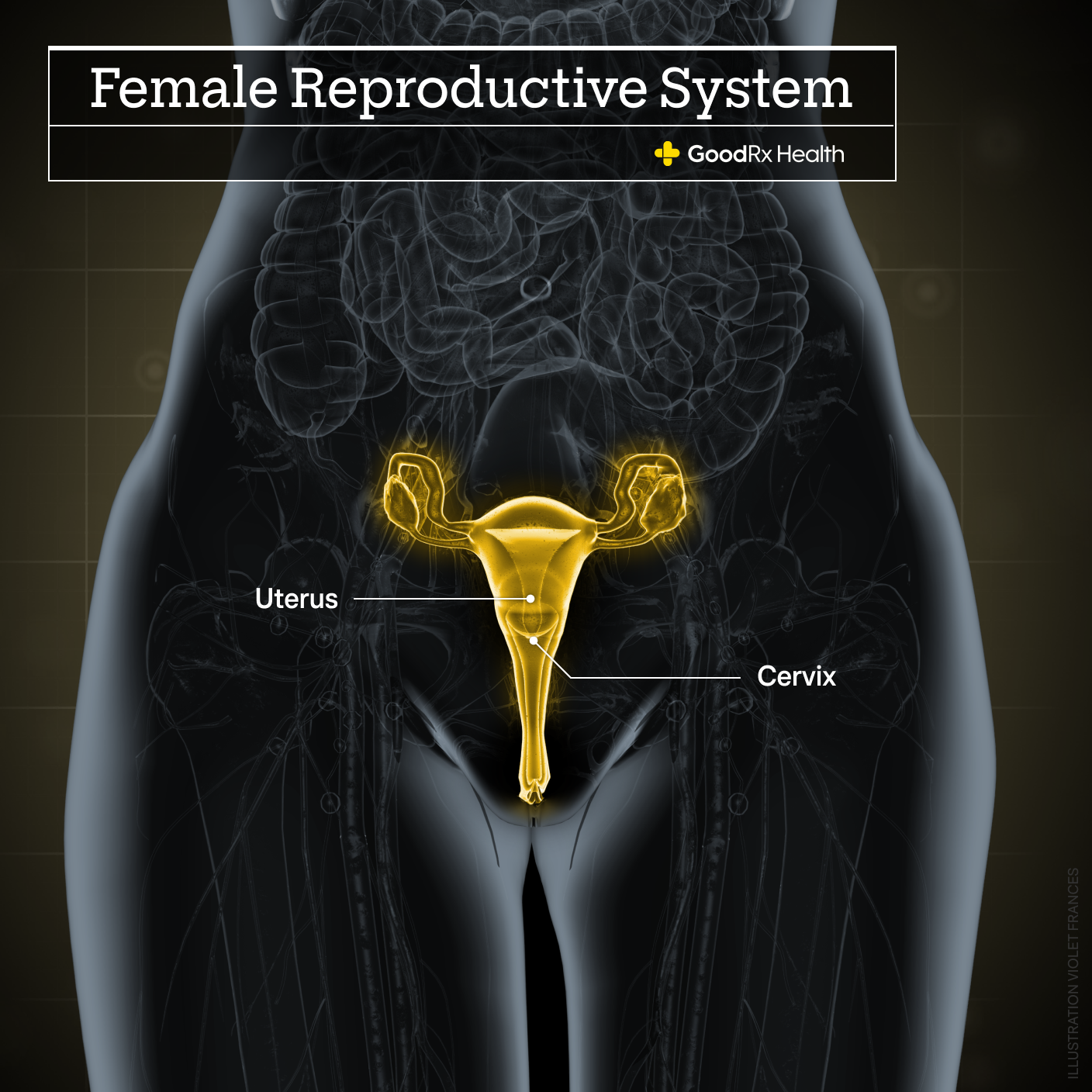

Cervical cancer refers to cancer of the cervix, which is the lower part — or neck — of the uterus.

Each year, there are over 12,000 new cases of cervical cancer in the U.S. Around the world, it is the fourth most common cause of cancer in women.

Cervical cancer, especially at very early stages, may not have any symptoms. It can also be curable. This is why screening is so important — screening can catch early, precancerous changes before symptoms even start.

When symptoms do happen, they can include:

Vaginal bleeding — including between periods or after intercourse

Unusually heavy or long menstrual periods

Pain during sex

A change in your normal vaginal discharge

Bleeding after menopause

Pain in the back or pelvic area

The main risk factor for cervical cancer is the human papillomavirus (HPV) — a common virus that can be passed between people during sexual contact. This means that if you have HPV, you are at higher risk for developing cancer of the cervix. You can have HPV without knowing it, too.

Other risk factors for cancer of the cervix include:

Smoking

Having multiple sexual partners

Having a weak immune system

Cervical cancer is one of the most preventable cancers today. Getting screened regularly can help prevent it.

What is the difference between cervical screening and a Pap smear?

Cervical screening includes two quick and easy tests — the Pap smear (also called Pap test) and the HPV test. These tests work in different ways, but they can both flag anyone who is at higher risk of developing cervical cancer to stop the process before it becomes too serious.

Here we talk more in depth about both of these tests.

The Pap smear

A Pap smear is usually done during a regular pelvic exam. Your provider will collect a small sample of cells from the cervix which will be looked at under a microscope. The Pap test can show if the cells of the cervix are healthy or not. Abnormal cervix cells may mean the cells are cancerous, but more commonly, the cells show changes that are “precancerous.” This means that — given time — those cells could turn into cancer of the cervix.

Abnormal cells are usually described as low grade or high grade. This refers to how slowly or quickly the cells could turn into cancer. Low-grade changes usually don’t turn into cancer and can go back to normal on their own. Women with low-grade changes may need to be tested more often to make sure the abnormal changes improve or don’t get any worse.

Women with high-grade changes may need additional testing and treatment. Even high-grade changes can take 3 to 7 years to turn into cancer, so screening can usually catch these changes very early. If you have an abnormal Pap smear result, you will probably need screening more often. You may also need some other tests.

Does cervical screening also test for HPV?

Yes. The second part of cervical screening is the HPV test. This looks for certain types of HPV that can cause cervical cancer.

HPVs are common viruses that can be transmitted between people during sexual contact. There are over 200 HPV types (also called genotypes). More than 40 different HPV types can infect the genitals. Most people who are sexually active will have an HPV infection at some point and not even realize it. But your immune system can clear HPV infections most of the time.

HPV types are categorized either as low risk or high risk. Both low-risk and high-risk HPV types can cause genital warts, which can be treated. A high-risk HPV infection (usually with HPV type 16 or 18) can increase the risk of getting certain types of cancer, including:

Cervical cancer

Oropharyngeal cancer (mouth and throat)

Genital cancers (anus, penis, vulva, and vagina)

The HPV test can be done at the same time as the Pap test. This is called co-testing. It’s worth having both done at the same time if you need them both, as the HPV sample is collected in the same way as the Pap smear — through a pelvic exam. It can also be done separately, and can be used as a screening test every 5 years.

Some studies have shown that the HPV test may be better than just the Pap smear at protecting against cervical cancer, but it may not be as good as getting co-tested with a Pap smear. If your HPV test is abnormal, you may also need to get a follow-up Pap smear. Talk to your provider about which screening tool is best for you.

What happens during a cervical screening?

Cervical screening can be done as part of the pelvic exam. During the screening, your provider uses an instrument called a speculum to open your vagina, which helps them see your cervix. They then put a small brush-like tool into the vagina, which is used to collect a sample of cells from different parts of the cervix. The cells are sent to a laboratory where they are looked at by healthcare professionals under the microscope. The cells can be used for both the Pap smear and the HPV test, depending on what your provider ordered.

Is cervical screening painful?

Cervical screening is not painful for many women. But it can cause mild pain or discomfort similar to menstrual cramps. The process usually takes less than a minute, so any discomfort usually goes away quickly.

After cervical screening, you may experience some light bleeding or spotting. This is very common and usually goes away within a few hours.

Who should get a cervical screening?

All people with a uterus and cervix who are between age 21 and 65 should have regular cervical screening.

Below age 21, screening is not needed, even if you are sexually active.

After age 65, screening is no longer needed — as long as you’ve had good screening up until that point and you aren’t at a higher risk for cervical cancer (like if you have a weakened immune system).

People who have had their uterus and cervix removed do not need to be screened unless they have a history of abnormal Pap smears or cervical cancer.

At what age should I start getting cervical screenings?

If you have a uterus and a cervix, you need to start having regular cervical screening after turning 21, and most people should get them until they are 65 years old.

How often should you have a cervical screening?

How often you need cervical screening depends on your age, your medical history, and the results of your most recent screening test.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends these screening guidelines:

Between age 21 and 29, women should have a Pap test every 3 years.

Between age 30 and 65 years, women should have one of these three tests: 1) a Pap smear every 3 years, 2) an HPV test every 5 years, or 3) a combined Pap and HPV test every 5 years

Some people may need to be screened more often. If any of the following are true for you, talk to your healthcare provider to make sure you are getting the right screening tests at the right time:

You have had cervical cancer before.

You are HIV positive.

You have a weakened immune system.

You were exposed to synthetic estrogen diethylstilbestrol (DES) before birth (if you’re not sure, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s DES Self-Assessment Guide can help you figure out how likely it is that you were exposed).

Do I still need cervical screening if I have had the HPV vaccine?

Yes — even if you’ve had the HPV vaccine, you still need to get regular cervical screening. The HPV vaccine is extremely effective in protecting against the common HPV types that can cause cancer, but it doesn’t protect against all HPV types. There is still a chance you could get cervical cancer even if you’ve had the HPV vaccine. This is why you need cervical screening even if you’ve been vaccinated.

The Pap test result: What to expect

Getting your Pap test results can be stressful. Here’s some information to help you know what to expect and when. We’ll walk you through the different results you could get and what they mean. Be sure to talk to your healthcare provider about your specific situation and results in order to come up with the best plan for you.

Let’s start with how long results take to come back. Then, we’ll talk about the HPV result — that one’s the easiest one to understand. Finally, we’ll talk about the Pap smear. That’s a bit more complicated.

How long do cervical screening results take?

It can take up to 3 weeks to get your screening results back, but the timing can vary depending on your provider and the lab used.

What is a normal HPV test result?

The HPV test can either be negative or positive.

A negative test means that you don’t have any of the HPV types that have been associated with cancer. For most women, this means that you can wait 5 years before getting another HPV test.

A positive test means that you have one or more of the high-risk HPV types that have been associated with cancer. It’s important to remember that this doesn’t mean that you have cancer or that you will get cancer. It just means that you may be at higher risk of getting cervical cancer, and may need additional testing or treatment.

If you have a positive HPV test and a normal Pap test, your provider may recommend that you be rechecked in a year. This is because your immune system may be able to attack the virus and get rid of it on its own.

What does my Pap smear result mean?

Normal

A normal test (also called a negative test) means that no abnormal cell changes were found in your cervix. This is good news, but you still need to get regular screening since abnormal changes can still happen.

After a normal Pap test, your provider may recommend that your next screening test be in 3 years. If you have a normal HPV test at the same time, you may be able to wait 5 years until your next screening.

Unsatisfactory Pap test results

This means that the laboratory couldn’t perform the test. This could be because there weren’t enough cells collected, or the cells could have been hidden by blood or mucous. Your provider will ask you to come back and have another Pap test done. This is frustrating, but it’s not necessarily bad news.

Abnormal

Having an abnormal Pap test (also called a positive test) can definitely make you worry. But it does not mean that you have — or will develop — cervical cancer.

Abnormal Pap tests are actually quite common: About 16% of women have had one at some point. An abnormal test just means that some abnormal cells were found in your sample.

What happens if my Pap test is abnormal?

If you have an abnormal test, you are not alone. In fact, about 16% of women have had an abnormal cervical screening test (including an abnormal Pap test, an HPV test, or both).

Remember, in the U.S., about 70% of women over age 18 had a Pap test within the last 3 years, and there are over 12,000 new cases of cervical cancer each year. This means that only a very small percentage of abnormal screening tests will actually turn into cancer.

Still, if you’ve had an abnormal result, you’re likely to have a ton of questions about what comes next. This will depend on what type of abnormality was found. The cervix has two main types of cells — squamous and glandular — and the abnormal changes can involve either type of cell.

Here are some common abnormal test results and possible next steps.

Atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASC-US)

This is the most common Pap test result. It means that there were some mild abnormal changes seen in the squamous cells (which line the surface of the cervix). These changes could be from HPV or from something else, like hormones or a yeast infection. Your provider may do an HPV test (if you haven’t had one), or may just repeat your Pap test in a year.

Atypical glandular cells (AGC)

This means that some glandular cells were found that don’t look normal. Glandular cells are found in the cervical canal. With an AGC result, usually more testing is needed, which may include a biopsy (see below for information about biopsies).

Low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (LSIL)

Other terms for this include mild dysplasia or cervical intraepithelial neoplasia I (CIN I). This means that there were low-grade changes found. This could be from an HPV infection and may go away on its own, but more testing is usually recommended. This may include a biopsy to see if there are more severe changes that need to be treated.

Atypical squamous cells, cannot exclude HSIL (ASC-H)

This means that there are some changes that could be a high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (see below), and treatment may be needed. But since the changes weren’t definite, more testing is usually required, possibly including a biopsy.

High-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL)

Other names for this include moderate or severe dysplasia, or CIN 2, CIN 2/3, or CIN 3. These changes are more serious and could turn into cervical cancer if not treated. A biopsy — and possibly treatment — are usually recommended.

Adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS)

This is an advanced area of abnormal growth found in the glandular cells of the cervix. If this is not treated, it could become cancer (cervical adenocarcinoma).

Cervical cancer cells

Sometimes, cancer cells can be found in a Pap test. This is very uncommon in women who have regular screening since the screening tests catch any abnormal changes very early.

Possible next tests

Having an abnormal screening test may mean getting screened more often, or it may mean you will need additional testing. Here are some common procedures your provider may order if you’ve had an abnormal screening test.

A colposcopy is a procedure that helps your provider examine your cervix and vagina more closely to look for any signs of disease. It’s similar to a pelvic exam, but it uses a colposcope, which is a magnifying instrument with a light.

During a colposcopy, your provider may put an acetic-acid solution (similar to vinegar) or some other type of solution on the cervix. This helps highlight any areas that may have suspicious, or abnormal, cells.

If there are abnormal areas, your provider will likely take a biopsy, which is a small tissue sample to be looked at under the microscope. This is the best way to see if the changes are precancerous, cancer, or something else.

There are a few different types of biopsy you can have. Depending on the situation, some biopsies are able to remove all the abnormal tissue, and no further treatment is needed.

Colposcopic biopsy: During a colposcopy exam, forceps are used to take a small sample of tissue from the surface of the cervix. This may cause discomfort or pressure but is usually not painful.

Endocervical curettage (endocervical scraping): A small spoon-shaped instrument (a curette) or a brush is used to get a sample of tissue from the inside of the cervical canal. This may cause some cramping pain and light bleeding after the procedure.

Cone biopsies: If either of the above biopsies is abnormal, your provider may need to do a deeper biopsy in order to diagnose, or treat, any atypical areas. These are called cone biopsies because they remove a cone-shaped piece of tissue from the cervix. There are two main types of cone biopsies: 1) LEEP (Loop Electro-Surgical Excision Procedure): This uses a thin, electrified wire to get a tissue sample. This is usually done with local anesthesia in the office. 2) Cold knife cone biopsy: This uses a knife or laser to remove a larger piece of tissue. This is usually done with some type of anesthesia at the hospital.ssue. This is usually done with some type of anesthesia at the hospital.

These procedures can help determine if you have any abnormal (precancerous) or cancerous cells. In some cases, the biopsy will be enough to remove all of the abnormal tissue, and no more treatment is needed. Your provider may recommend that you follow up with another screening test.

If the biopsy shows that cancer is present, more testing may be needed to see if and how far the cancer has spread. This can include imaging studies (like a chest X-ray or CT scan), which provide a look inside the body. Your provider will work with you to determine the appropriate next steps.

How can I lower my risk?

There are some steps you can take to help lower your risk of cervical cancer.

Get screened: This is the most important — and effective — step you can take to lower your risk. Make sure you follow the recommended screening guidelines, and if you have any questions, be sure to reach out to your healthcare provider. January is Cervical Cancer Screening Awareness Month, so mark your calendar to take this important step for your health.

HPV vaccine: Certain types of HPV are the main risk factor for getting cervical cancer. The HPV vaccine can help prevent you from getting those infections. The HPV vaccine is recommended for girls and boys between 11 and 12 years old, and for everyone up to age 26 if not received earlier. And in some situations, adults between 27 and 45 years may benefit from the vaccine. The vaccine is usually given in either two or three doses.

Don’t smoke: Studies have shown that smoking is a significant risk factor for developing cervical cancer. Not smoking — or quitting smoking — can help lower that risk.

Use condoms: HPV can be transmitted between sexual partners, and using condoms can help lower the risk of getting HPV.

Limit your number of sexual partners: Having more sexual partners can increase your risk because it increases your risk of being exposed to HPV. Limiting your number of partners can help lower that risk.

Keep in mind

The Pap and HPV tests are both extremely effective tests. In some studies, HPV and Pap tests both had high specificity, but the HPV had a higher sensitivity. Sensitivity and specificity are medical terms used to see how effective a test is.

A higher sensitivity means that the HPV test is somewhat better at catching all the women who have abnormal changes, and not missing women who have abnormal changes (called false negative tests). And when both tests are used together, the sensitivity is even higher.

Both Pap and HPV tests have high specificity, meaning that women with a normal cervix didn’t have abnormal test results (called false positive tests).

If you have cervical cancer, your treatment and prognosis (the chance of recovery) depend on many things, including the stage of the cancer. Cancer stage is determined by the size of the cancer and if it has spread to other parts of your body.

The main treatment options for cervical cancer include:

Surgery

Radiation therapy

Chemotherapy

Immunotherapy

Targeted therapy (treatment that finds and attacks cancer cells without hurting normal cells)

More information and resources

References

Best study we found

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. (2018). Screening for cervical cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Journal of the American Medical Association, 320(7), 674-686.

American Cancer Society. (2020). Treating cervical cancer. Retrieved from https://www.cancer.org/cancer/cervical-cancer/treating.html

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. (2018). Cervical cancer screening FAQs. Retrieved from https://www.acog.org/womens-health/faqs/cervical-cancer-screening

BBC News. (2019). Smear test top tips: How to make cervical screening more comfortable. Retrieved from https://www.bbc.com/news/newsbeat-47452760

Cancer.Net. (2019). Cervical cancer: Symptoms and signs. Retrieved from https://www.cancer.net/cancer-types/cervical-cancer/symptoms-and-signs

Canfell, K. (2019). Towards the global elimination of cervical cancer. Papillomavirus Research, 8, 100170.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016). HPV vaccine information for young women. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/std/hpv/stdfact-hpv-vaccine-young-women.htm

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019). Cervical cancer: What are the risk factors? Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/cervical/basic_info/risk_factors.htm

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019). Cervical cancer: What should I know about screening? Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/cervical/basic_info/screening.htm

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019). Health, United States, 2018 — data finder. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/hus/contents2018.htm#Table_034

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020). Basic information about HPV and cancer. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/hpv/basic_info/index.htm

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020). Interactive DES self-assessment guide. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/des/consumers/guide/index.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020). United States cancer statistics: Data visualizations. Retrieved from https://gis.cdc.gov/Cancer/USCS/DataViz.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020). U.S. cancer statistics data visualizations tool. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/cervical/statistics/index.htm

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020). Vaccine and preventable diseases: HPV vaccine recommendations. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd/hpv/hcp/recommendations.html

Chido-Amajuoyi, O. G., & Shete, S. (2019). Prevalence of abnormal cervical cancer screening outcomes among screening-compliant women in the United States. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology, 221(1), 75-77.

Deacon, J. M., Evans, C. D., Desai, M., et al. (2000). Sexual behavior and smoking as determinants of cervical HPV infection and of CIN3 among those infected: A case-control study nested within the Manchester cohort. British Journal of Cancer, 83(11), 1565-1572.

Gargano, J., Meites, E., Watson, M., et al. (2014). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Manual for the surveillance of vaccine-preventable diseases. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/surv-manual/chpt05-hpv.html

Mayrand, M., Duarte-Franco, E., Rodrigues, I., et al. (2007). Human papillomavirus DNA versus Papanicolaou screening tests for cervical cancer. New England Journal of Medicine, 357(16), 1579-1588.

National Cancer Institute. (2020). HPV and cancer. Retrieved from https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/risk/infectious-agents/hpv-and-cancer#cancers-caused

National Institutes of Health National Cancer Institute. (2019). Next steps after an abnormal cervical cancer screening test: Understanding HPV and Pap test results. Retrived from https://www.cancer.gov/types/cervical/understanding-cervical-changes

National Institutes of Health National Cancer Institute. (2020). Cervical cancer screening (PDQ) – patient version. Retrieved from https://www.cancer.gov/types/cervical/patient/cervical-screening-pdq

Olusola, P., Banerjee, H. N., Philley, J. V., & Dasgupta, S. (2019). Human papilloma virus-associated cervical cancer and health disparities. Cells, 8(6), 622.

Rodrigeuz-Alvarez, M. I., Gomez-Urquiza, J. L., Husein-El Ahmed, H., et al. (2018). Prevalence and risk factors of human papillomavirus in male patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(10), 2210.

Ronco, G., Dillner, J., Elfstrom, K.M., Tunesi, S., et al. (2014). Efficacy of HPV-based screening for prevention of invasive cervical cancer: follow-up of four European randomized controlled trials. Lancet, 383(9916), 524-532.

Roura, E., Castellsague, X., Pawlita, M., et al. Smoking as a major risk factor for cervical cancer and pre-cancer: results from the EPIC cohort. International Journal of Cancer, 135(2), 453-466.

Sachan, P. L., Singh, M., Patel, M. L., & Sachan, R. (2018). A study on cervical cancer screening using Pap smear test and clinical correlation. Asia-Pacific Journal of Oncology Nursing, 5(3), 337-341.

Stoler, M.H., Austin, M., & Zhao, C. (2015). Point-counterpoint: Cervical cancer screening should be done by primary human papillomavirus testing with genotyping and reflex cytology for women over the age of 25 years. Journal of Clinical Microbiology, 53(9), 2798-2804.

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. (2018). Screening for cervical cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Journal of the American Medical Association, 320(7), 674-686.