We’ve seen portraits of those who could afford to commission them, and they exude confidence, pride, and self-satisfaction. On the contrary, the paintings in this gallery are meant to ridicule and tease human deficiencies and weaknesses, often at the expense of others.

In Flanders during the 1500s, you might look around at your fellow humans and see them living it up: gorging themselves with food and drink, dancing, and living in excess. Such actions could lead to greed, lust, and other follies. In the face of their sins, all humans could do was admit their shortcomings and laugh at themselves (or at the ones portrayed).

The scenes in these paintings hold up a mirror to us: They are often full of jokes, pranks, and witty double-meanings. But the punchline is always deadly serious: Don’t be like the fools and sinners in these artworks, otherwise you will never get to heaven.

Jan Massijs

South Netherlandish, 1509–1575

Rebus: The World Feeds Many Fools

About 1530

Oil paint on panel

The Phoebus Foundation, Antwerp

Image © The Phoebus Foundation, Antwerp

The painting on your left is a rebus—a word puzzle— that the artist has challenged us to solve. The key is reading the image like a written text—left to right and top to bottom—and decoding the pictorial signs according to the sound of the words they represent. In the painting we see the letter D, a globe, a foot, and a fiddle above a fool stuffing his mouth with porridge. When said in Dutch, they read “The world feeds many fools,” a popular proverb. These puzzle games were all the rage!

Quinten Metsys

South Netherlandish, 1466–1530

Keep Your Mouth Shut

About 1528

Oil paint on panel

The Phoebus Foundation, Antwerp

Image © The Phoebus Foundation, Antwerp

106. Quentin Metsys (and Jan Massys), An Allegory of Folly, c. 1525-1530

Narrator: Stranger and stranger… This “fool” or jester has donkey’s ears and a rock for a brain that protrudes from his forehead. The rooster on his cap suggests his chatter is just so much boastful crowing. On his stick perches his rather indiscreet miniature friend. We can expect them to mock each other – but then turn on us!

Katharina Van Cauteren: We, the onlookers, we tend to think of ourselves very highly. But this fool, he knows that he's a fool. So he's one up on the rest of us. But it's a good thing that he puts a finger on his mouth, because we are all just fools like him, but luckily … he won't tell anyone!

Narrator: The scene would have been appreciated for its sly message, but also for its bawdy humor – irresistible to a 16th century audience.

The painting is by Quentin Metsys, who had an incredibly successful career as an artist in Antwerp in the early 1500s. He trained his sons to follow in his footsteps, as did many artists. Flemish and Italian artists were always feeding off one another’s innovations and intriguingly, the Metsys family were no exception.

Katharina Van Cauteren: By the 16th century painters from the Netherlands, they start looking at the new things that are happening in Italy. And one of the new things is Leonardo da Vinci, who is painting, or drawing these caricatures. And you see that somehow Quentin Metsys, and his sons, they must have known these drawings somehow. And you see how they reflect in their own paintings.

Pieter Pietersz

South Netherlandish, about 1540/41–1603

The Barley Counter

About 1560–70

Oil paint on panel

The Phoebus Foundation, Antwerp

Image © The Phoebus Foundation, Antwerp

107. Pieter Pietersz, The Counter of Groats, c.1560-1600

Narrator: We might think this old man is doing something useful – helping in the kitchen! But for a sixteenth century viewer, the painting would have been hilarious. A man acting as a kitchen maid? No way! And “counting out grains of barley”, in contemporary slang, meant nit-picking - according to Flemish people, an annoying and decidedly female trait.

Katharina Van Cauteren: So, this man behaves like a woman, and they found that very, very funny. Feminism was still a long way off, I would say. And it's also got to do with the emergence of a new set of social rules.

Narrator: The new class of wealthy, urban Flemish citizens was trying to find their place in society between the nobility and the peasants. And in doing so, to establish their own codes of behavior against those of people lower down the scale. So they loved to gather round and laugh together at pictures of peasants acting foolishly for entertainment.

Katharina Van Cauteren: Netflix wasn't invented yet, so you looked at paintings!

Frans Verbeeck

South Netherlandish, active 1531–1570

The Mocking of Human Follies

About 1550

Oil paint on canvas

The Phoebus Foundation, Antwerp

Image © The Phoebus Foundation, Antwerp

The market in this scene bustles with activity. It is swamped with fools on every side: piles of tiny fools are delivered in baskets, sacks, and cauldrons, while another shipload has just docked in the harbor in the background. Along the way, the miniature fools infect everyone else with their madness. The revelers fail to notice that the inn on the far right is on fire. And yet the warning could not be clearer: the inn represents the fires of hell, in which all these fools will eventually burn.

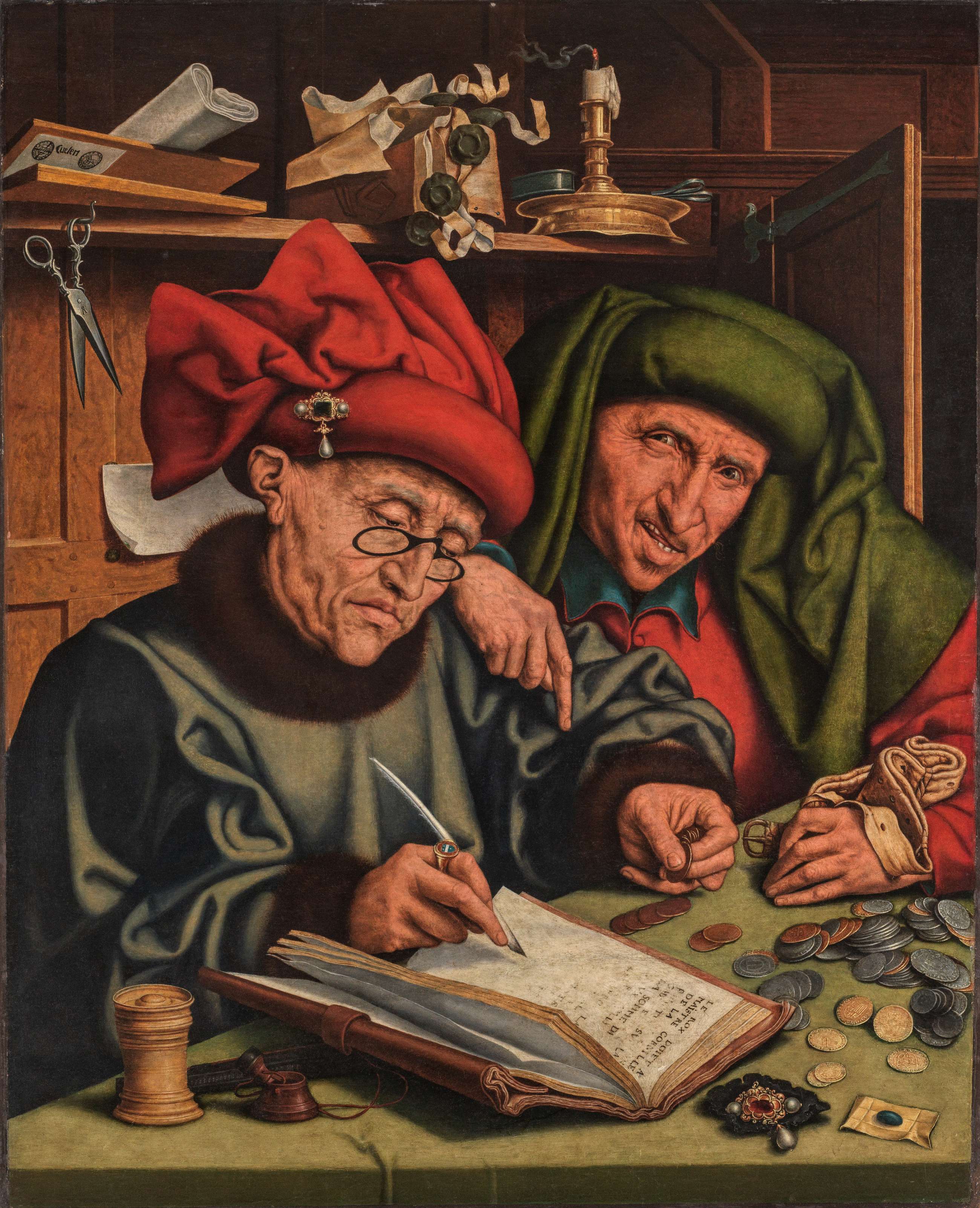

After Quinten Metsys

South Netherlandish, 1466–1530

Tax Collectors

About 1530

Oil paint on panel

The Phoebus Foundation, Antwerp

Image © The Phoebus Foundation, Antwerp

This image is part of a tradition meant to address the contemporary problems of greed stemming from the boom-and-bust cycles of the Antwerp economy during the 1500s. The painting references tax-farmers, private individuals who profited personally from collecting taxes and thus have an interest in squeezing every last coin from the citizens’ pockets. The ugliness of greed is evidenced in the way the artist distorts the facial features of the figure to the right. The burnt-out candle on the shelf reminds us life is too short and only a fool would waste it in sinful pursuits.

Saints, Sinners, Lovers, and Fools: 300 Years of Flemish Masterworks is co-organized by the Denver Art Museum and The Phoebus Foundation, Antwerp (Belgium). It is presented by the Birnbaum Social Discourse Project. Support is provided by the Tom Taplin Jr. and Ted Taplin Endowment, Keith and Kathie Finger, Lisë Gander and Andy Main, the Kristin and Charles Lohmiller Exhibitions Fund, the Samuel H. Kress Foundation, Christie's, the donors to the Annual Fund Leadership Campaign, and the residents who support the Scientific and Cultural Facilities District (SCFD). This exhibition is supported by an indemnity from the Federal Council on the Arts and the Humanities. Promotional support is provided by 5280 Magazine and CBS Colorado.