The Perpetual Labor of Jaques by the Limbourg Brothers

In Medieval France, the peasantry — derided as Jacques Bonhomme — perpetually toiled for the noble class.

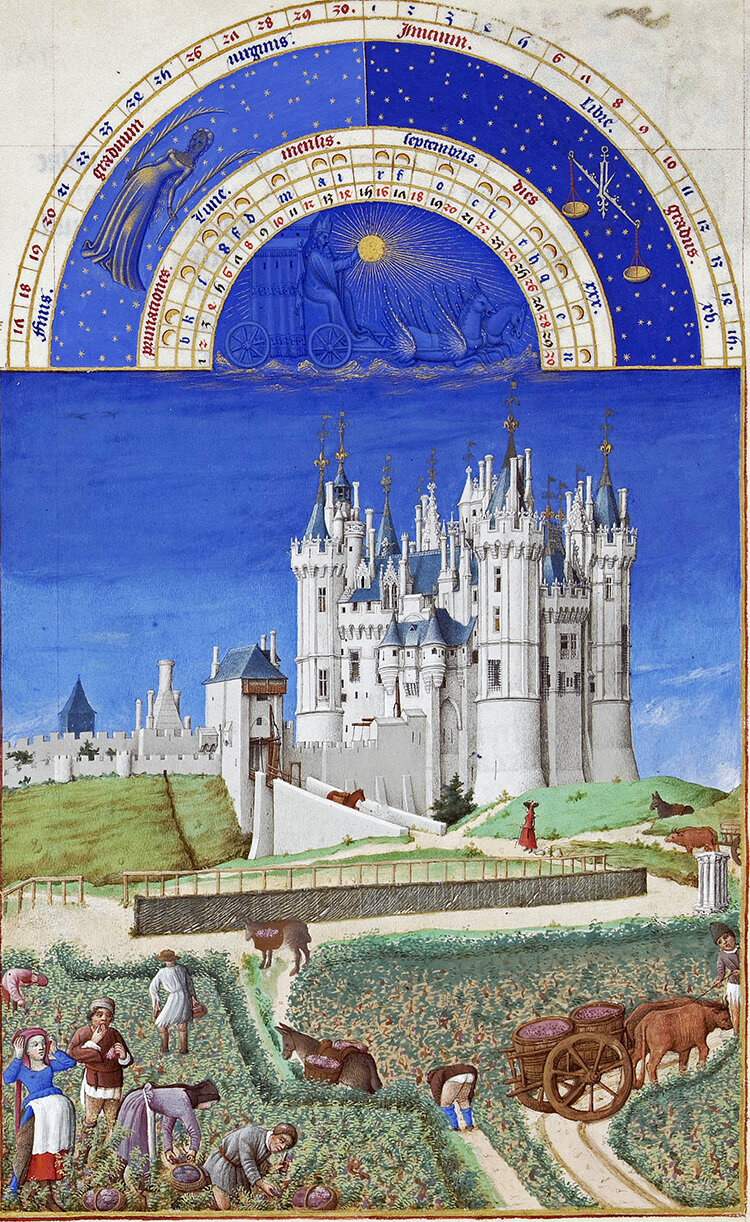

Cover photo: October: Tilling the field, from Les Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry, colors and ink on vellum, by the Limbourg Brothers (1413-1416). Via Maquetland.

The Art of Labor

At the height of the Industrial Revolution in the United States, American workers — including children — suffered twelve hour work days and seven day work weeks. Labor Day originated in 1882 as an annual mass rally in New York organized by socialists and leftist organizations to demand shorter hours, higher pay, safer working conditions, and a labor holiday. President Grover Cleveland would declare Labor Day a federal holiday in 1894.

COVID-19 has revealed who are the essential workers and who performs the unnecessary “bullshit jobs”. This once-in-a-century pandemic has also demonstrated the global interdependency of resources, labor, and supply chains — what we commonly refer to as globalization.

Millions of Americans have lost their jobs, and likely their healthcare. This has inspired me to create a new series on the art of labor through the centuries, with a focus on how work has been valued and represented.

Medieval France

Paris was settled in the geographic region referred to as the Paris Basin, which provided conditions suitable for farming. By the 3rd century BCE, the area was occupied by the Gallic tribe of the Parisii, until their defeat by the Romans. Following the collapse of the Roman Empire in 476 AD, the region was divided into an assortment of kingdoms.

Ongoing disputes between the kingdoms of France and England culminated in the official start of the Hundred Years’ War in 1337. King Jean (John) II — the second king of the Valois dynasty — attempted several truces to no avail; in 1356, he was captured and held for ransom by the English. Jean II had five children, the eldest son — the dauphin — would succeed him as King Charles V.

Decades later, a young girl from a small French village claimed witness to divine visions that Charles VII, heir of Charles VI, was the rightful king of France. In her 1429 Letter to the English, peasant-girl-turned-military-commander Jeanne d’Arc (Joan of Arc) demanded, “Surrender to the Maid, who is sent from God, the King of Heaven, the keys to all the good cities that you have taken and violated in France.” Inspired by Jeanne d’Arc’s execution in 1431, the various kingdoms of the French region would unite by the end of the 15th century.

Books of Hours

The book of hours is a type of Christian devotional book offering prayers in honor of the Virgin Mary, popularized in the 13th century. These books were used by the masses and nobility alike. Books of hours were comprised of several parts, but were known particularly for the Hours of the Virgin —including psalms, hymns, and prayers dedicated to the Virgin Mary — for which the books was named after.

Les Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry are considered to be the finest book of hours manuscript in existence. As states the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Jean, the Duke of Berry, “was the son, brother, and uncle of three successive kings of France (Jean the Good, Charles V, and Charles VI). He lived during a time of almost continual unrest between England and France, a period known as the Hundred Years’ War”. Despite the opposition of his brother, the dauphin Charles V, Berry came to control at least one-third of the territory of France.

Translated from French as The Very Rich Hours, “The Très Riches Heures was a label given in the legal process of monetary evaluation after the duke’s death in an inventory of his goods, thus locating it as an object of real, not symbolic, value. We do not know how the duc de Berry referred to it, being just one of sixteen books of hours he owned,” noted art historian Michael Camille. The Limbourg Brothers — Herman, Paul, and Jean — utilized not only gold leaf in the book’s creation, but also liquid gold.

Berry kept multiple items from the Limbourg Brothers, first employing the young boys when they were teenagers, after the death of his brother Philippe for whom the brothers were originally working. The prodigal Limbourg Brothers were sons of a wood-carver and nephews of Jean Malouel, the court painter to the Queen of France.

The brothers completed Les Belles Heures at the turn of the century and a few years later, after having refined their skills, began Les Très Riches Heures. Tragically, the brothers would not see the manuscript to completion as all three would die in 1416, along with the patron Jean, likely from an early outbreak of the Black Plague. The Duke had spent so heavily on art and treasure, there was no money to pay for his funeral. The book of hours would eventually be completed by Jean Colombe in 1485.

Les Très Riches Heures

Books of hours began with a perpetual calendar that recorded major feast days and local saints days. The calendar often featured corresponding signs of the Greek zodiac and various labors traditionally associated with the months. Les Très Riches Heures is best known for this section. The exquisite full-page calendar illustrations include lunettes painted in the lavish pigment lapis-lazuli, decorated with stars and the Greek charioteer sun god Helios. On the calendar page for October, the Limbourg Brothers have illustrated libra on the left and scorpio on the right.

According to Gardner’s Art through the Ages: The Western Perspective, Volume II,

“Here, the Limbourg brothers depicted a sower, a harrower on horseback, and washerwomen, along with city dwellers, who promenade in front of the Louvre (the French king’s residence at the time, now one of the world’s great art museums). The peasants do not appear discontented as they go about their assigned tasks. Surely this imagery flattered the duke’s sense of himself as a compassionate master. The growing artistic interest in naturalism is evident here in the careful way the painter recorded the architectural details of the Louvre and in the convincing shadows of the people and objects (such as the archer scarecrow and the horse) in the scene.

As a whole, Les Très Riches Heures reinforced the image of the duke of Berry as a devout man, cultured bibliophile, sophisticated art patron, and powerful and magnanimous leader. Further, the expanded range of subject matter, especially the prominence of genre subjects in a religious book, reflected the increasing integration of religious and secular concerns in both art and life at the time.”

In 1411, for New Years, the Limbourg Brothers gifted Jean, duc de Berry, with a counterfeit wooden book, a good-natured joke that a book could be judged by its cover. The young brothers — born in the 1380s — must have had a healthy sense of humor, as illustrated by the presence of magpies eating the seeds just dropped by the peasant in the calendar page above.

As writes Professor of English, Ashby Kinch, Les Très Riches Heures is a testament to “the decisive role of art as a unique witness to the subjective perspective of cultural history”. The wonderful naturalism employed by the brothers foreshadowed the growing trends of realism.

The Louvre

Founded in 1190, the construction of the Louvre fortress was ordered by Philippe II, King of France, during the Crusades, to protect the walls of Paris near the vulnerable river Seine. The fortress was destroyed in 1546, at the request of Francis I, in order for a royal residence to be built on the site.

In 1793, following the French Revolution, the Louvre would open as the Musée Central des Arts in the Grande Galerie. The public institution would represent of a new egalitarian vision of France. “The museum was a symbol of the Enlightenment ideals that informed the revolution–public display of art that was previously held in a royal collection,” writes Kat Eschner for Smithsonian Magazine.

Later, Baron George-Eugene Haussmann lead the construction of new water and sewage pipes as well as train stations, and replaced the medieval alleyways with straight broad boulevards and standardized building heights; he gentrified the city by removing low-income residents to construct apartments for the upper classes. Haussmann’s renovation of Paris (1853-1870) was a vast public works program commissioned by Emperor Napoléon III to become the city recognized today.

Jacquerie

“During the fourteenth century the French peasants and serfs, despite their incessant labour, had no means of existence but what was left them by their lords, who dealt as they pleased,” wrote Professor Louis Raymond de Vericour.

“Everywhere the peasant was denominated Jacques Bonhomme, meaning the good-natured fool,” Vericour explained. “When a Jacques was spoken of it was intended to imply a ridiculous, stupid, clownish human being, until the day when that word became a fearful subject of horror, and by a sudden change and contrast it signified a ferocious beast.”

The peasant class of Jacques eventually banded together in 1358 to destroy fortresses, homes, and goods belonging to the noble class. Just two years prior, King Jean II had been captured by the English, discrediting the power of the French nobility.

As summarizes Senior Lecturer at the University of St Andrews, Justine Finhaber-Baker, “The reason nobles lived in fortresses was because they could physically coerce the peasants into handing over their surplus (whilst they themselves remained often exempt from royal taxation), and the reason they could do that was because they were a warrior aristocracy who lived in fortresses.”

The insurrection proved unsuccessful. Parisian rebels were defeated at Meaux by Gaston Phoebus of Foix and Jean III de Grailly, followed by massacre.

“There was a pause, when suddenly all the nobles and knights recommenced to kill and destroy. All the houses and churches were plundered. The city was set on fire. It burnt during a fortnight, and was totally consumed. They afterwards overran the whole country round Meaux, slaughtered indiscriminately every human being, burnt the villages, and committed ravages yet greater than what had been experienced from the English and from the great companies,” described Vericour. “[T]he nobles avenged themselves because their victims had dared to avenge the iniquities and infamies they had so long endured.”