Zaha Hadid was an explosion of fearless, impolite, aggressive talent onto a profession terrified of itself

Zahahadid rgb

Illustration by Max Knicker

It is hard to recapture the state of British architecture in 1982. Modernism of any sort was at the nadir of its reputation, blamed for all manner of social ills by both Left and Right. The cul-de-sac became a spatial ideal for both Labour councils and Tory developers. Public buildings were seldom proposed, let alone built, but when a competition was held for one on Trafalgar Square, it became the pretext for a culture war that recalled the rhetoric of 1930s dictatorships. In ‘high’ architecture, an odd collective decision had been made that design was a matter of decoration and semiotics, where the most important problem was how the building itself ‘spoke’: to the user, and to the area around, preferably politely and deferentially. So the competition-winning design for The Peak, a club and café to be built on a hill in Hong Kong, must have seemed as though it was from another planet, where the response to the post-1968 criticism of Modernism was to make it harder, harsher and weirder; and where rather than making a new building harmonise with the existing landscape, the architect forced it to become the landscape itself. It’s no surprise its designer didn’t build anything in Britain for nearly 30 years.

The peak blue slabs by zaha hadid

An exquisite early drawing of The Peak poised amid Hong Kong’s thrilling topography. Image: Zaha Hadid Foundation

Whatever else you think about Zaha Hadid, remember this moment, this explosion of an absurdly fearless, aggressive, impolite talent onto a profession which had become utterly terrified of itself, and terrified of modernity. It’s customary to compare Hadid’s early work to the Soviet avant-garde, and that – plus the Stadtkrone designs of the German Expressionists – is about as far as you have to go back to find something as reckless, though there are also some analogies to be made in the more geological side of Brutalism (the mounds and walkways of the South Bank Centre, long a Hadid favourite). What Hadid seemed to take most from the Soviets, the Constructivists and especially the Suprematists, was the notion of a ‘station between painting and architecture’, a term coined by the trained architect El Lissitzky to describe his apparently unbuildable yet oddly blueprint-like paintings. But unlike the contemporary work of OMA – or Hadid’s graduation project Malevich’s Tektonik, which imagines the painter’s Architektons taking over the Thames around Hungerford Bridge – The Peak is not retro, and it’s not a ‘reference’. Unlike the other later-to-be-famous, Derrida-quoting architects lumped together as ‘Deconstructivists’, she had no obvious plans for attacking the ‘metaphysics of presence’. And unlike those in the ’80s who mined the Soviet 1920s in music and graphic design, she had no obvious interest in its politics. These were forms, floating free of the ambiguous Soviet experiment.

The question was whether this could ever actually be built, and whether the spatial effects suggested by her drawings, like the ecstatic The World (89 D+egrees) – planes and polygons erupting in oblique angles out of cranked, churning landscapes – could ever actually be felt in real space. Hadid’s first built work suggested otherwise. The social housing block she designed for the IBA in Berlin in 1987 is fine on its own terms, but it bears only the most tenuous relation to the accompanying paintings, where the forms that feel so fixed on the ground surge outwards. The first building that suggested she could actually get at least some of that into actual space was the Vitra Fire Station in 1993 (originally published in the AR that year) quickly found to be functionally deficient – and later rather mildewed, like a neglected piece of 1960s Brutalism: not a comparison that would have bothered its architect.

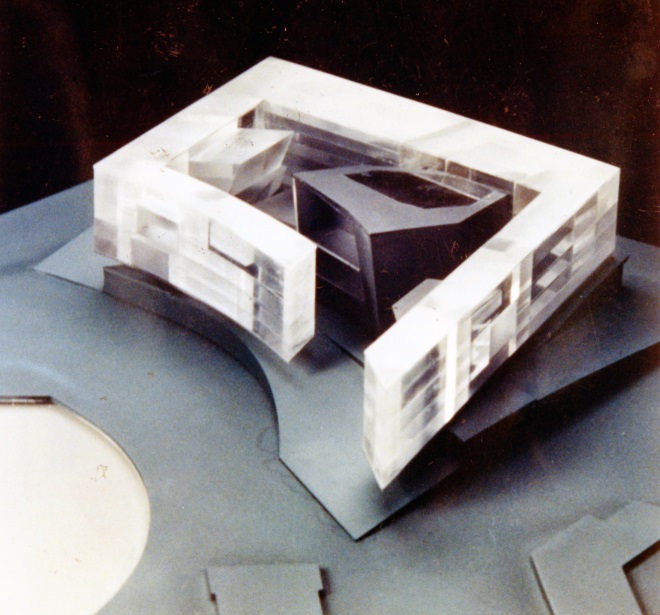

Bpm media wales cardiff opera house 01

Model of Cardiff Bay Opera House, which was scandalously unrealised. Image: Media Wales

Hadid, in her fairly few public pronouncements, often praised the most criticised postwar urban projects – Alexanderplatz, the Tricorn Centre – cheerfully unbothered by their general reputation. You can look at the reaction to the Cardiff Bay Opera House, won in competition and then rejected in the mid-1990s, as a horror at the values of the Brutalist 1960s coming back, at a recurrence of what Owen Luder approvingly called ‘sod you’ architecture. It was replaced with Percy Thomas’s Millennium Centre, and in exchange for a design which attempted an abstract dialogue with the sweep of the bay and the constriction of the site, Cardiff got a building which stressed local ‘reference’ and semiotics at every point, from the Anglo-Welsh inscription to the use of local stone. The scandal made clear that Britain, even in the apparently sympathetic Blair years, with its liking for ‘icons’, was not a suitable place for Hadid’s highly abstract version of Modernism.

C06aeg

Berlin apartment block designed for the 1987 IBA. Image: imageBROKER / Alamy

The buildings which will endure among her built work were all constructed in succession at the turn of the 21st century. They are heavy, distorted, and based on massive volumes of reinforced concrete. The Cincinnati Contemporary Art Center featured a clash of hulking grids, Malevich gone physical, inserted into a typical American metropolitan street plan. The MAXXI museum in Rome, criticised for its sloping walls – as if installations and sculptures didn’t take up as much space as painting in the average contemporary art gallery – had a similar heft, and an obsessive use of flowing, intersecting circulation. And the Phaeno Science Centre in the German motor manufacturing town of Wolfsburg is extraordinary, where Hadid finally frees from Brutalist and Constructivist sources into prolapse of surging concrete.

Many of these works have a strangely laconic relationship to the ex-industrial sites where they’re built. Contemporary with Phaeno is the BMW Factory in Leipzig, which is often photographed and discussed as if it was the entire factory, rather than a very specific corner of a much larger, metal-clad big shed. ZHA were not commissioned to design the whole building – just the building’s entrance, which they did with all the whipcrack energy of their 2000s work. A long, skinny concrete volume leads you from the car park into what is essentially little more than a reception hall, into which they’ve run a part of the production line, with cars being pieced together by white-coated workers, continuously. It runs at an upper level above your head as you wait, as a visitor, for your tour to start; as a worker, for your shift to begin; or as a corporate visitor, to dazzle you with the efficiency and beauty of the BMW assembly line. The materials that Hadid used here – unpretentious metal and concrete – are the same as those of the immense shed around it, but unlike in the factories of, say, Modernist cult figures like Albert Kahn or Owen Williams, there is a disjunction between production and architectural spectacle, with the two running simultaneously, but not in the same place, with the break obvious.

Zha bmw central building helene binet 032 copy

At BMW’s Leipzig plant car carcasses glide through the office interior. Image: Hélène Binet

This became all the more clear in the later, and much flimsier, Glasgow Transport Museum, a fussily engineered logo visible only from space, but also, a big Clydeside shed just opposite the BAE shipyards in Govan. It is about as banal in expression and monumental in scale as the shipyards, but far more materially extravagant. There was always something sad in the way that the hugely wasteful but fascinating, bristling and bafflingly complex steel skeletons of these later ‘Parametric’ buildings would be covered with perfunctory shiny cladding, as if to give the buildings the sort of smooth contours that would previously have been achieved through concrete work, constantly testing the possibilities and forcing the material to perform implausible feats.

Even so, on formal grounds it’s odd that work so grounded in the tradition of the avant-garde was so often criticised by defenders of historical Modernism. This was arguably because so much of Hadid’s later work – like that of practically every major contemporary architect – was in the despotic petrol states of the Persian Gulf.

Iraq postage stamp zaha hadid tc

Hadid depicted on an Iraqi stamp

As an Arab and a woman she was constantly and tediously exoticised by critics who were inclined to pick over her clothes, her domestic arrangements and her manner, in a way that would be inconceivable for an Eisenman or a Rogers. She also became a focus for criticism of profession-wide amorality, something which was hardly helped by Hadid’s bluff and occasionally litigious responses to criticism and an evidently thin skin.

‘There was always something sad in the way that the hugely wasteful but fascinating, bristling and bafflingly complex steel skeletons of these later ‘Parametric’ buildings would be covered with perfunctory shiny cladding’

These buildings entered an increasingly Rococo territory, and began to incorporate entire landscapes, most famously in the Heydar Aliyev Centre in Baku. They worked best on a tabula rasa, where it helped not to ask what was being cleared out first, and who was doing the clearing. However, it is this precisely landscape approach that makes her later buildings interesting. Hadid’s paintings, where entire cityscapes are undergoing some sort of process of warping and seismic overthrow, were never really about individual buildings. In fact, when you look at what the proposal was actually for, like that for her mid-’80s entry to the London ‘Grand Buildings’ competition, you’ll find something much more prosaic than the paintings imply. Things like the Aliyev Centre, because the aggressive clearing of land gave Hadid so much space to play with, also finally gave her the space to create the exhilarating geological formations and cities-within-cities her thought always implied.

Gettyimages 523579048

The proto-geological formation of Dongdaemun Design Plaza in Seoul. Image: Inigo Bujedo Aguirre / Getty

A particularly good example of this is the Dongdaemun Design Plaza, in Seoul. Although South Korea since the 1990s had no longer been a dictatorship, the ‘DDP’ was forced through by an authoritarian mayor, erasing an important market, whose traders were promised a relocation that never came. If you approach it via the teeming Russian and Central Asian market nearby, the first sight is of an enormous metal-clad lump on a traffic island, with no obvious connection except wide roads with very heavy traffic. Cross that, though, and finally, you’re there, in one of those paintings, in a totally three-dimensional space. Concrete bridges plunge into and between a series of galleries and malls, in the expensively ‘organic’, curvaceously Expressionist manner of late ZHA; they run up huge flights of stairs to parks shaped into Brutalist hillocks, and then curve downwards to meet, and submerge, a fragment of Seoul’s medieval city wall, the only piece of the area’s surroundings that Hadid seems to have shown much interest in.

3014552 zahasketchbookindexa

Hadid’s sketchbooks showing her interactions and explorations

Like a High Modernist project such as the Barbican, it is an internal landscape, which makes sense mostly only when you’ve passed a threshold. Unlike it, the thrills and spills are extreme, with functionality and rationality sacrificed to an almost hedonistic sense of sensuous affect. What is sad is that, bar some obligatory sweeping and swooping staircases, the interiors are poor – mostly windowless, often with meanly low ceilings, an afterthought. The three-dimensional landscape of the paintings was finally there, existing, in reality. What went into it was something of an irrelevance.

When she won the RIBA Gold Medal in 2016, Hadid gave an address that might have been more defensive than valedictory, stating a firm belief in ‘progress’, against ‘traditionalism’ – but what if ‘progress’ meant a society as grossly unequal as Qatar? Even so, Hadid’s most important built legacy will not be in the country she lived in for most of her life. That’s a weird corpus – a brackish cancer care centre in Kirkcaldy, an over-engineered swimming pool in Stratford constructed for the London Olympics, that big shed in Glasgow, a value-engineered gallery extensionin Hyde Park. Two works stand out. Evelyn Grace Academy, in Brixton, where a mean, disciplinarian programme inside is defined to the outside by one breathtaking moment, where a running track surges beneath the classrooms; the other is her last completed British building, the Middle East Centre at St Antony’s College in Oxford, a small-scale pavilion in a garden, clad in reflective panels, with a peculiar dollopy shape that looked like it had been squeezed out of a tube.

Download

As Hadid became a recognisable architectural brand she turned her hand to bags, furniture and even shoes

The Middle East Centre, which was a rare late solo work by Hadid herself, in its materials literally reflected – but certainly didn’t try to emulate – the Victorian and Brutalist buildings around it. Instead, it tried to provide something else, something new, that wasn’t beholden to concepts like ‘context’ or the ‘vernacular’, but which was strongly attuned to place and particularity. Because of this rejection of all classical values, at the end, she was perhaps as unfashionable – in the UK, at any rate – as she was in 1982, although vastly richer and more successful. ‘Why should 21st-century London look like Schinkel’s Berlin?,’ she asked in her RIBA address, and you know who she was talking about. The Middle East Centre won the annual award for ‘worst building’, doled out by Private Eye’s Piloti in 2015. ‘Modernismus’, refusal to genuflect to heritage, rootless cosmopolitanism. She should have worn Piloti’s hatred with pride.

This piece is featured in the AR’s March 2018 issue on Women in Architecture – click here to purchase a copy

Architectural Review Online and print magazine about international design

Architectural Review Online and print magazine about international design