Coronavirus restrictions have forced many of us to find imaginative room in small things, but last week I received a pleasant reminder of previous excursions to sublimity on the grand scale. The British Art specialists Lowell Libson and Jonny Harker sent me a link to their new online exhibition ‘Good Prospects’. The selection includes a Ruskin watercolour that I have long known, but only from a century-old reproduction, and it took me back to blithe times over twenty years when I made a photographic expedition to more-or-less exactly the same spot.

John Ruskin

The Aiguilles of Chamonix from below Les Houches, 1842

Watercolour and pencil heightened with white on grey wove paper, 13 × 18 ⅛ inches, 330 × 462 mm

With Lowell Libson & Jonny Harker, 2020

Provenance: Robert Ellis Cunliffe of The Croft, Ambleside, d.1902; Mrs Cunliffe (1912); Private collection, Australia; Private collection, UK, from whom purchased 2007 by Lowell Libson, to 2020 when exhibited by Lowell Libson & Jonny Harker in virtual exhibition ‘Good Prospects’ April 2020 as ‘Aiguilles of Chamonix near Les Houches, 1842’, repr colour; £45,000.

References: Ruskin 1854 Diary MSS list as ‘14 Aiguilles of Chamouni, from Les Ouches 1842’; Works 38/240, no. 398 as ‘Aiguilles of Chamouni, from Les Ouches (1842). No. 14 in R.’s list; w. c. (12¾ x 17½). Mrs. Cunliffe. Exh. R.W.S. 313, M. 88. Reprod., 35, Pl. 20 as ‘Chamouni’.’; David Hill, ‘Perfection, I should call it’: John Ruskin’s Personalised Guide to Switzerland, 1843’ in British Art Journal, Vol.13, no.1, Spring/Summer 2012, p.64, n.40; David Hill, ‘Ruskin drawings at King’s College, Cambridge: #1 Isolino di San Giovanni from Lago Maggiore, Evening’ in http://www.sublimesites.co, 2 March 2014 at https://sublimesites.co/2014/03/02/ruskin-drawings-at-kings-college-cambridge-1-isolino-di-san-giovanni-from-lago-maggiore-evening-2/; Libson-Yarker online exhibition ‘Good Prospects’, 2020 at https://www.libson-yarker.com/exhibitions/good-prospects-landscape-drawings-from-our-racks/aiguilles-of-chamonix-near-les-houches [accessed 09.04.2020]

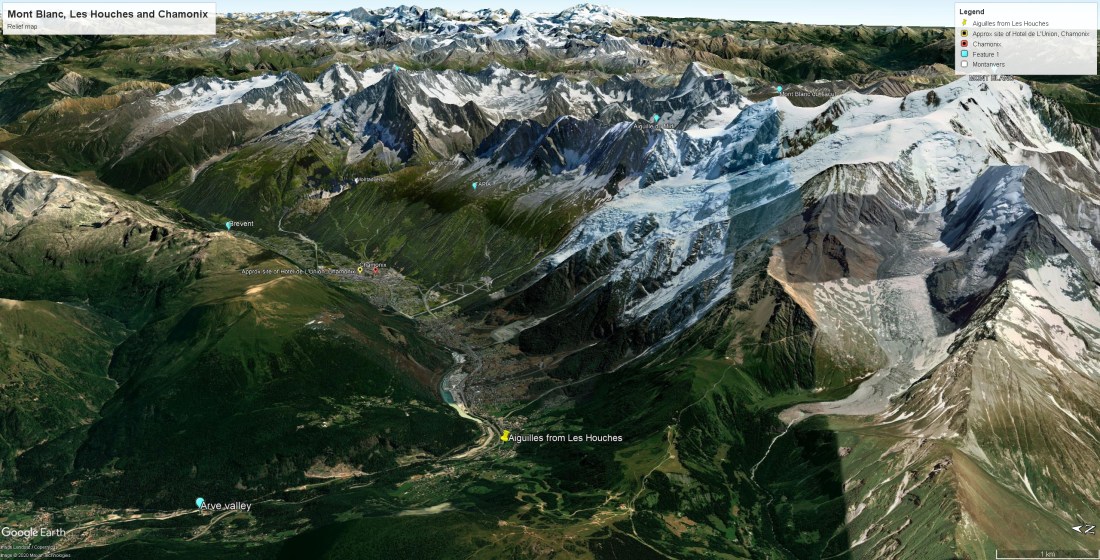

Ruskin’s viewpoint is a little way down the Arve valley from the village of Les Houches. We can see the river towards the left and the spire of Les Houches church to the right. The viewpoint provides one of the most comprehensive panoramas of the line of Aiguilles towering over the Chamonix valley. From left to right we see the Aiguilles Verte, Charmoz, Blaitiere, Plan, and Midi (above the church spire) culminating at the right with the peak of Mont Blanc de Tacul. The summit of Mont Blanc itself stands beyond the top right corner of the composition and the village of Chamonix is just hidden in the distance behind the bluff to the left.

[Click on image to open full size, then use your browser’s ‘back’ button to return to this page]

In actual fact my photograph is taken from a viewpoint very slightly higher and further right than Ruskin’s view. Ruskin’s exact position can be plotted by the intersection of the crest of the Cretes du Taconnaz with the summit ridge of Mont Blanc to Tacul, and the bead of the church spire on the Aiguille du Midi. Work on the ‘Route Blanche’ motorway to Chamonix, completed in 1990, altered the foreground detail from Ruskin’s time. The bluff that occupies the centre of Ruskin’s watercolour was blasted, backfilled and almost completely obliterated by the new carriageway.

The re-emergence of the watercolour reminds me that I have a good deal of unfinished business with Ruskin. I have planned all manner of grand projects on Ruskin’s Alpine drawings but only a few things have seen the light of day. There are a few articles on http://www.sublimesites.co [click here] and back in 2012 I wrote up a wonderful Ruskin letter for the British Art Journal (‘Perfection, I should call it’: John Ruskin’s Personalised Guide to Switzerland, 1843’, Vol.13, no.1, pp.54-67). Over the years I have been compiling a database of Ruskin in the Alps, and now count eight hundred and fifty-eight items, plus scores more that I haven’t got round to entering. One day, maybe.

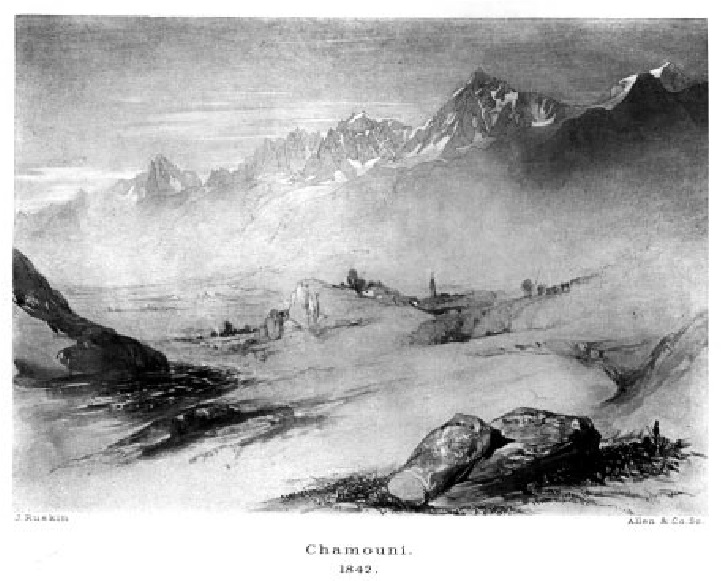

I knew of this subject from its black and white reproduction in the Library Edition of The Works of John Ruskin (Vol.35, pl.20).

Ruskin himself dated the watercolour to 1842 in a list of sixty-four Chamonix drawings made in his diary for 1854 (Works 5/xxi-xxii). It is no.14 as ‘Aiguilles of Chamouni, from Les Ouches 1842’.

Its first private owner appears to have been Robert E Cunliffe, a Manchester solicitor who retired to ‘The Croft’ at Ambleside in the last year of the nineteenth century.

Photograph by Professor David Hill, 28 March 2014

Following Ruskin’s death in 1900, numerous works came onto the market and Cunliffe managed to assemble a significant group before his own death in 1902. His collection descended in the family and was exhibited at the Abbot Hall Art Gallery in Kendal in 1969. At that time James S Dearden published a study of the collection “The Cunliffe Collection of Ruskin Drawings” in The Connoisseur. 171.690 (August 1969) pp. 237–40. After 1981 the collection was divided up. The largest part went to Abbot Hall but seven particularly fine examples were bequeathed to King’s College, Cambridge. In 2014 I started to write up the King’s drawings in detail one by one [click here] and so far have completed four. I had hoped to raise support for that work, but without success. Perhaps working on this drawing of Les Houches might prompt me to resume work on the final three.

To return to our present theme: In 1842 Ruskin was twenty-three years old, just graduated from Oxford, and making his third visit to Chamonix. In 1833 his first sight of the Alps had fixed in him a sense of where his true calling was to be found. At Chamonix in 1842 he found his vocation to explore the most profound knowledge of nature, especially as it was embodied in the art of J.M.W.Turner. On the way home he began to compose ‘Modern Painters’, the first volume of which was published in May of 1843.

His diary for this year is at Yale University Library and, although kept inconsistently, it does provide valuable documentation of his activity during his tour to the Alps. He travelled with his parents, although they are rarely mentioned, and their route took them from Calais through France to Geneva. They arrived in Chamonix by the 17th June and stayed four weeks.

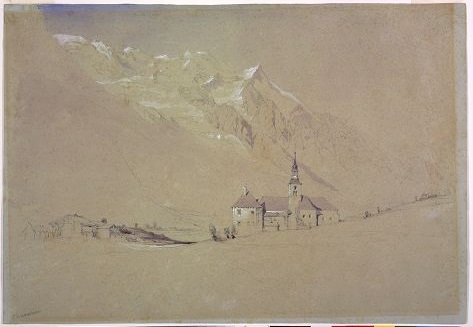

Hotel de L’Union, Chamonix, c.1820

Coloured aquatint.

Photograph taken by Professor David Hill, 30 June 2011

They put up at the Hotel de l’Union , now disappeared, but built in 1816 and the first of the grand hotels to be built in Chamonix. In the 1830s Murray’s Handbook, p. 291 considered the Londres to be one of the finest hotels in the Alps, so standards at the Union must have been exceptional for the Ruskins to have made it their preferred base.

[Image best viewed full-size. Click on image to enlarge, the use your browser’s ‘back’ button to return to this page]

By anybody’s standards the valley of Chamonix is a place of epic scale. The floor of the valley lies at over 3000 feet, the first shoulder over 6000, the crest of the Aiguilles about 12,000, and the summit of Mont Blanc at 15774. It is indeed a place against which to test one’s strength.

Ruskin started gingerly enough, recording on 17 June that he climbed half way up the Tapia. This is the glacier-strewn slope that extends from the foot of the aiguilles to the top of the shoulder, so even only half-way to the shoulder involves a climb of 1500 feet. Sensibly, he came down for fear of becoming tired.

The following day he climbed to the Montanvers at 6276 feet and ventured onto the ice of the Mer de Glace [see here]. At the age of twenty-three he quickly acclimatised and a week later on the 24th he climbed to the Flegere a point at 6158 feet on the north side of the valley that gives a spectacular view into the valley of the Mer de Glace opposite, and then climbed a thousand or 1500 feet further. On the 27th he went up to the Col de Balme at 7201 feet: On the 29th to within 300 feet of the top of the Brevent, which towers over Chamomix from the north at 8284 feet. On 30th to the Tapia, 1 July to the Montanvers again and on 11 July he made it to the summit of the Brevent.

By the standards of contemporary twenty-somethings at Chamonix, this might not seem altogether adventurous. In any case he might not have accomplished all of this on foot. On 4 July he records that he went up to the Pavilion de Belle Vue, a climb of 2591 feet from Les Houches, but the same entry records that he ‘rode down’ about 2.00. All the same, we can certainly say that he threw himself into the landscape with some physical vigour and could legitimately feel in the vanguard of Alpine afficionados.

Ruskin later said that he did very little drawing at Chamonix in 1842, but this is not borne out by the evidence. There are references in the diary to drawings made towards Argentiere, at Chamonix and of a Tadpole Stream on the road towards Servoz, plus a specific reference on 12 July to the present view: ‘Tuesday, down to.. Servoz. View of aiguilles just below Les Ouches, decidedly finest in valley.’ Surprisingly this subject is the only one of 1842 that is listed in the 1854 list, but I have collected records of seven others for the database. Why then did Ruskin list only one in 1854? It seems most likely that those listed were the drawings that actually had to hand. He continually gave drawings as gifts to friends and family.

My database includes the following;

The Aiguille du Dru seen over the Glacier du Bois from the floor of the Valley of Chamonix, sold Sotheby’s, 8 July 1982 no.154 as ‘The Matterhorn’, repr colour, est £2500-4000.

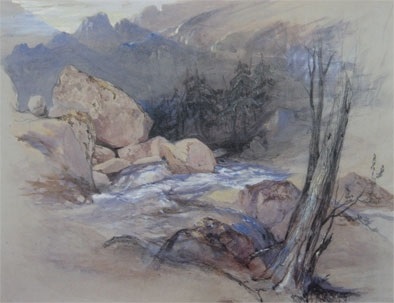

Rocks and Stream, Chamonix, Abbot Hall Art Gallery, Kendal.

Mont Banc from the Prieure, Chamonix, Fogg Art Museum, Harvard, USA

Mont Blanc with the Glaciers des Bossons and Taconnay, seen across the Arve valley from the pool of Les Galliards, below Chamonix, sold Sotheby’s 8 July 1982 no.155 as ‘An Alpine Valley’, repr colour, est £4-6000

Glacier des Bois and Aiguille Bouchard near Les Tines, Lancaster Ruskin Library, University of Lancaster, RF894

Mont Blanc with the Aiguilles, from above Les Tines, reproduced in the Library edition as Vol.4, frontispiece, when in the collection of Sir John Simon.

Chamouni in Afternoon Sunshine, or On the Road to Chamouni, given by Ruskin to his tutor Osborne Gordon, and reproduced in the Library edition as Vol.3, pl.4, when in the collection of W Pritchard Gordon.

At some stage I might secure an opportunity to write something at length about Ruskin and the Alps. My database includes one hundred and forty-seven subjects with Chamonix in the title, and perhaps as many more in the area of Mont Blanc. Many more no doubt remain to be catalogued. One day some Alpine venue might think of staging what could be a superb exhibition. For the present I’ll content myself with expanding the frame of the present drawing a little more.

In the months before setting out for Chamonix in 1842 Ruskin enjoyed two artistic initiations. Firstly he saw the set of Swiss watercolours and ‘sample studies’ that Turner showed to prospective clients through his dealer Thomas Griffith. Ruskin recognised these as the culminating point of Turner’s knowledge of nature at its most sublime. He even persuaded his father to order two finished examples. He also took lessons in painting from James Duffield Harding. The latter was a very successful drawing master, known for a distinctive sketching style using toned paper and white highlights, but also known as an associate of Turner and capable of producing work of Turnerian effect and grandeur.

Ruskin had already discovered the power of drawing when used as an analytic tool; as a way of entering into understanding; of piercing through prefiguration to glimpse the strangeness of the real. His recent experience at the University of Oxford had engendered an appreciation of the sophistication of academic understanding, but also of its limitations. He saw a fiercely penetrative sense of things embodied most perfectly in Turner, a man of no educational qualification or sophistication, but whose work contained deeper understanding of nature than anyone else had ever achieved in landscape. An understanding achieved through practice.

Drawing became Ruskin’s best and lifelong investigative apparatus and words the attempt to elucidate what he learned through [and embodied in] practice. One of the most superficial things he took from Harding was a certain stylishness of finish, but he learned quickly that finish was an artificial affectation, unless it contributed to the purpose of analysis and understanding.

In a letter to W. H. Harrison from Chamonix dated June 20, 1842 we can see how rapidly the conceits of finish were overwhelmed by experience. Harrison published Ruskin’s early attempts at Poetry in the magazine Friendship’s Offering, and appears to have expressed the hope for some new effusion about Chamonix:

“If I have not followed every suggestion you have made, it is only because I am so occupied in the morning—and so tired at night—with snow and granite, that I cannot bring my mind into a state capable of taking careful cognizance of anything of the kind. I cannot even try the melody of a verse, for the Arve rushes furiously under my window—mixing in my ear with even imaginary sound, and every moment of time is so valuable—between mineralogy and drawing—and getting ideas;—for not an hour, from dawn to moonrise, on any day since I have been in sight of Mont Blanc, has passed without its own peculiar—unreportable—evanescent phenomena, that I can hardly prevail upon myself to snatch a moment for work on verses which I feel persuaded I shall in a year or two almost entirely re-write, as none of them are what I wish, or what I can make them in time.” [Works 2/222]

The uselessness of poetic affectation is significant of what Ruskin came to consider as his proper Chamonix work, in that he set himself to slough off all conceits and conventions of the Alps, and come to know the area through the most painstaking, prosaic programme of study that he could muster, He made diligent records of clouds and weather effects, collections of rocks and minerals, botanical studies and some of the most penetrating and concentrated of all drawing studies of the area. In this drawing we can already see him working through the affectation of Harding’s style to a real appreciation of the distinctive cleavages and underlying dynamics of mountain geomorphology. We can also see the emergence of Ruskin’s lifelong interest in the relationship of macro and micro set out in the relationship of distant, middle distance and foreground forms.

Reflecting on this experience immediately after his return to England, the project gained an adamantine purity. Writing to his college tutor, the Rev. W. L. Brown in August 1842 he observed:

“Chamouni is such a place! There is no sky like its sky. They may talk of Italy as they like. There is no blue of any firmament visible to mortal eye, comparable to the intensity and purity and depth of an Alpine heaven seen from 6000 feet up. The very evaporation from the snow gives it a crystalline, unfathomable depth never elsewhere seen. There is no air like its air. Coming down from Chamouni into the lower world is like coming out of open morning air into an ale-house parlour where people have been sleeping and smoking with the door shut all night; and for its earth, there is not a stick nor a stone in the valley that is not toned with the majestic spirit; there is nothing pretty there, it is all beautiful to its lowest and lightest details, bursting forth below and above with such an inconceivable mixture of love and power—of grace with glory—its dews seem to ennoble, and its storms to bless; and with all the constant sensations of majesty from which you never can escape, there is such infinite variety of manifestation, such eternal mingling of every source of awe, that it never oppresses, though it educates you.’ [Works 2/223].

In beginning my own visit in 1999 I should probably have adopted more of Ruskin’s caution. Far from saving myself from getting tired, I decided that the best way to begin a walking tour of Mont Blanc would be to ascend to the top of the Brevent [on the cable-car, I might add] and then walk down to Les Houches. The first quarter was glorious, the second quarter, sufficient, the third quarter, excessive, and the final quarter a mere blur of cramping calves and jellied quads. In retrospect, attempting one of the longest and most sustained footpath descents in the whole Alps was ill considered.

In the morning descending the stairs to breakfast could only be accomplished in the seated position. Walking over the Col de Vosa, or at least down the other side to Contamines, was simply out of the question. So it was decided to grimace along the level path to Les Houches station, take this photograph along the way, catch the train down to St Gervais, and then take a taxi up to Notre Dame de la Gorge. From there the route headed consistently uphill for two days to the Croix du Bonhomme, and that proved surprisingly comfortable. The descent to Le Chapuieux was accompanied by [how shall I put this] some protestations, but after that normal progress was resumed. Suffice it to say that the person looking through the lens was less sparkling than the scene before him.

David Hill, 4 May 2020

Lovely. I wish I could afford an Alpine Ruskin, but it just can’t be. No-one drew the Alps like him, before or since.

Looks like all we can do is continue to press our noses to the window! DH

It is interesting that neither Lot 154 nor Lot 155 (8 July 1982) were actually sold. I wonder what became of them?